Written by Grace deVega

SDSU History Major, 2022

This quote is particularly fitting for this final blog exploring my process in designing the digital exhibit “Sound of Comics” for SDSU’s Center for Comics Studies. Of all of the academic endeavors I have undertaken while at SDSU, this one has felt the most like a journey. There have been multiple paths to tread, obstacles to overcome, and constant support and encouragement along the way. And now I have reached the end: You can access “Sound of Comics” here.

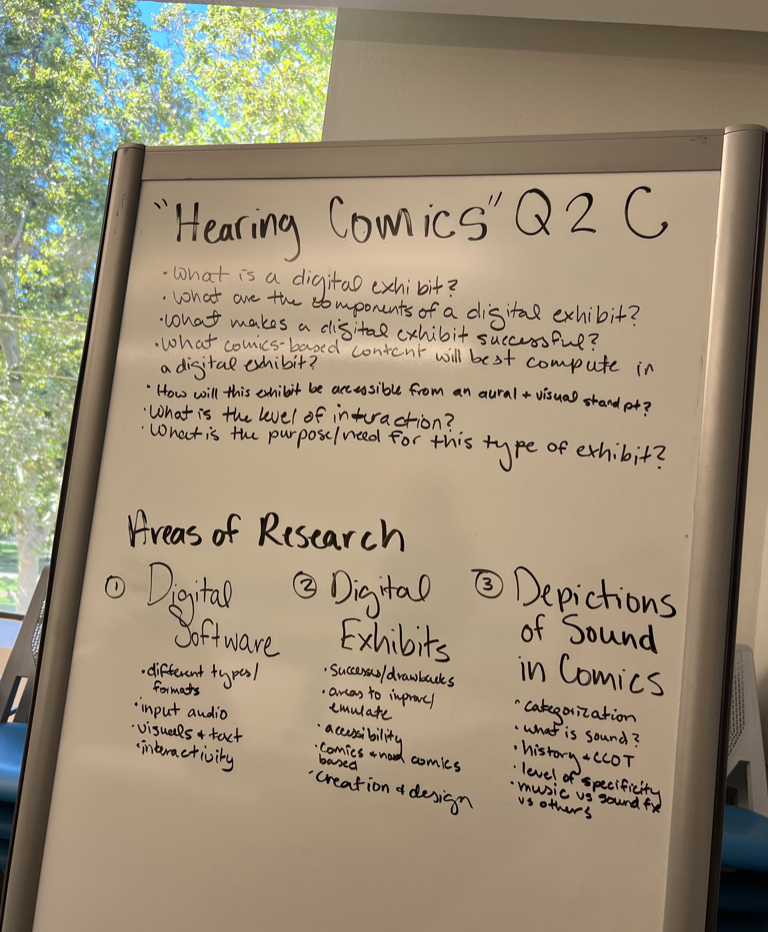

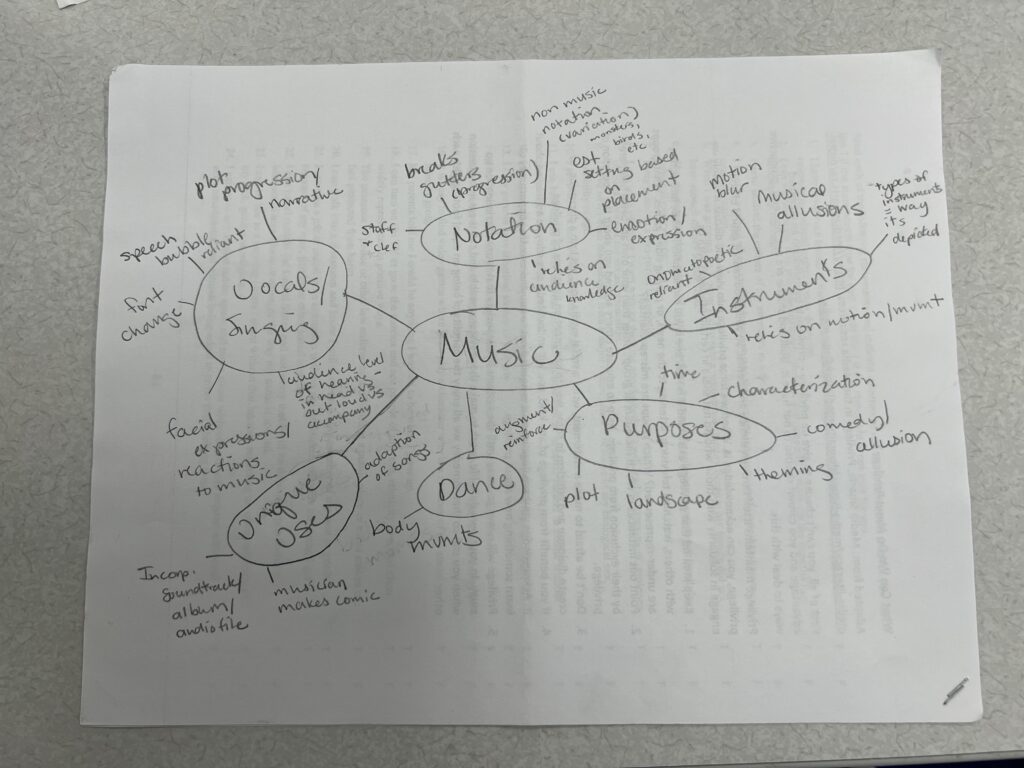

In terms of multiple paths, some of the most significant decisions I have made in the final part of this curation have pertained to paring down the content. I cultivated a substantial number of collection pieces — far more than could be included — after scouring the materials in the library and beyond. The process then became a task of figuring out connection points between the pieces and organizing them into a proper exhibit. Often, I created a visual guide to help me write down all of my ideas and begin building relationships between avenues of content.

As evidenced by this brainstorm web, I had several different avenues that I wanted to explore with music alone. I also knew that too many subsections would overwhelm my audience with text and images, so I selected specific pieces and paths to pursue, which helped the claims in the exhibit appear more intentional and direct. For instance, one path that I did not pursue outright was the notion of “Dance” in comics, but I still found ways to incorporate the dance-related ideas into some of the collection’s pieces. Each of the exhibit sections received similar treatment, and the end result was three major categories with several smaller subcategories that reinforced the ideas of their parent topics.

With reference to obstacles, most of the barriers that I faced dealt with translating the exhibit into its digital form. As I expected, there was a significant learning curve when first working with WordPress, which is the platform that I selected (having chosen from Omeka, Google Sites, Adobe, and a few other digital exhibit options). I watched several tutorials and made several unsuccessful attempts to figure out the system at the beginning. However, I eventually learned the tools of the platform, as well as figured out how to manipulate those tools to produce the content and design that I desired. Most of this work came through trial-and-error, which was difficult but ultimately rewarding when I was able to see the finished product of each section. In addition, I decided to format the layout of all of the pages before implementing their text and images which proved useful in building my confidence and knowledge of the platform while also ensuring their uniformity. Perhaps most importantly, I was able to overcome these challenges through the support of Dr. Pamella Lach, the Director of the Digital Humanities Center at SDSU. I met with Dr. Lach several times, and she helped me select WordPress as my digital platform, as well as offered advice on best practices throughout the process. Her support was particularly helpful when discussing accessibility with the website and making certain that the exhibit is compatible with screen readers and all other ADA compliances. I am so grateful for her assistance and insight.

To that final point about support, I have been fortunate throughout this entire process to receive advice and encouragement from a variety of sources. Along with the indispensable support of Dr. Lach, several other scholars have offered their perspective in improving my work and helping me examine sound in comics more thoroughly. Over the last month, I have had the privilege to interview several comics scholars, querying their understanding of sound in comics. I interviewed Dr. Barbara Postema, who studies wordless comics, to discuss comics that tell stories when conventional forms of sound are intentionally limited. Dr. Postema explained the role of images, pictographs, and expression lines in replacing alphabetic symbols when figures communicate. For instance, she referenced the dashed dialogue lines in Hawkeye #19, which she labeled “asemic,” or lacking in semantic content, as a key example of this type of wordless sound conveyance. She mentioned the frustration that audiences experience when encountering communication in this form, and I found such insight extremely helpful when creating the “Disability and Sound” section of the exhibit.

I also had the opportunity to interview Dr. José Alaniz, a comics scholar and professor at University of Washington, Seattle. Our conversation covered a wide array of topics pertaining to sound in comics, and one of my biggest takeaways from Dr. Alaniz was the ability of sound to both reinforce and distort the reality of the comic. We discussed the “mimetic function” of certain sounds, such as including a pre-existing song within a scene because it establishes the setting in time and in its similarity to the world of the audience. At the same time, Dr. Alaniz pointed out that depictions sounds are often “toyed with,” as he called them, to underscore the unfamiliarity of the landscape and exacerbate the divide between the world of the comic and the world of the reader. His perspective proved invaluable when I discussed environments in the “Music” and “Sound Effects” sections of the exhibit.

Lastly, this project would have been “dead air” without the guidance and supervision of Librarian Pamela Jackson and Dr. Elizabeth Pollard. Pam Jackson provided me with some of the first comics that I read for the exhibit, and she, along with the rest of the Library’s Special Collections and University Archives team, have been incredibly helpful, thoughtful, and considerate over the course of my research, especially when I spent hours in their archives poring over comics. Similarly, Dr. Pollard always made herself available to answer questions, provide feedback, read over text that I had written, and connect me with people that could support my efforts. I have grown so much as a student, scholar, and fan of comics under her guidance. Lastly, Dr. Pollard and Librarian Jackson have shown genuine enthusiasm for my work throughout the entire process, which has helped me stay motivated and reassured in the steps I had taken, even when I questioned myself.

So, while this may be the end of my journey into sound in comics, I could not be more proud of the work I have done or more appreciative of the people who helped me get there.

Grace deVega (she/her) is a Fourth Year History and Political Science student at San Diego State University. She previously won the President’s Award at the SDSU Student Research Symposium and 1st Place in her Division at the CSU Research Competition for her research into the impacts of the 1986 Philippines People Power Movement on nonviolent revolutions. She has also played clarinet for the past twelve years, including in the SDSU marching and concert bands, which is where her passion for music and aural studies derives.