Written by

Raechel Dumas, Associate Professor, History

San Diego State University

“Manga and Japanese History” maps a cultural history of modern Japan through manga produced at the juncture of significant historical moments and transformations. We will trace how evolutions in manga reflect developments including the rise of mass print culture; rapid urbanization; the violence of the Asia-Pacific War; atomic discourse in the postwar decades; eruptions of violence and neonationalist responses in the recessionary period; evolving gender and sexual paradigms; the emergence of new youth cultures; and the increasing proliferation of technology into every part and parcel of Japanese life.

Situating manga as primary source texts, we will analyze how an array of genres—including propaganda, autobiography, romance, magical girls, science fiction, horror, and slice of life—reflect evolving paradigms of Japanese subjectivity and nationhood. Moreover, we will devote substantial attention to how works of manga reflect social justice concerns in their engagements with gender and sexual roles and relations. racial and ethnic violence, disability stigma and erasure, and the uncertain conditions of life in the recessionary period, among other themes.

For example, in his analysis of race and power in the Pacific War, historian John Dower describes an image published in 1942 in the manga magazine Osaka Puck: “A soldier drawn in a heroic mode . . . wields a broom as he strides out of Japan into greater Asia, sweeping Uncle Sam and John Bull off the globe.”1 In this class, we will analyze a series of similarly propagandistic examples alongside Dower’s cultural history of Japanese wartime racial formations. In doing so, we will delve into how artists leveraged the medium to reify wartime discourses on Japan as the “leading race” (shidō minzoku), in turn legitimizing the nation’s imperial project.

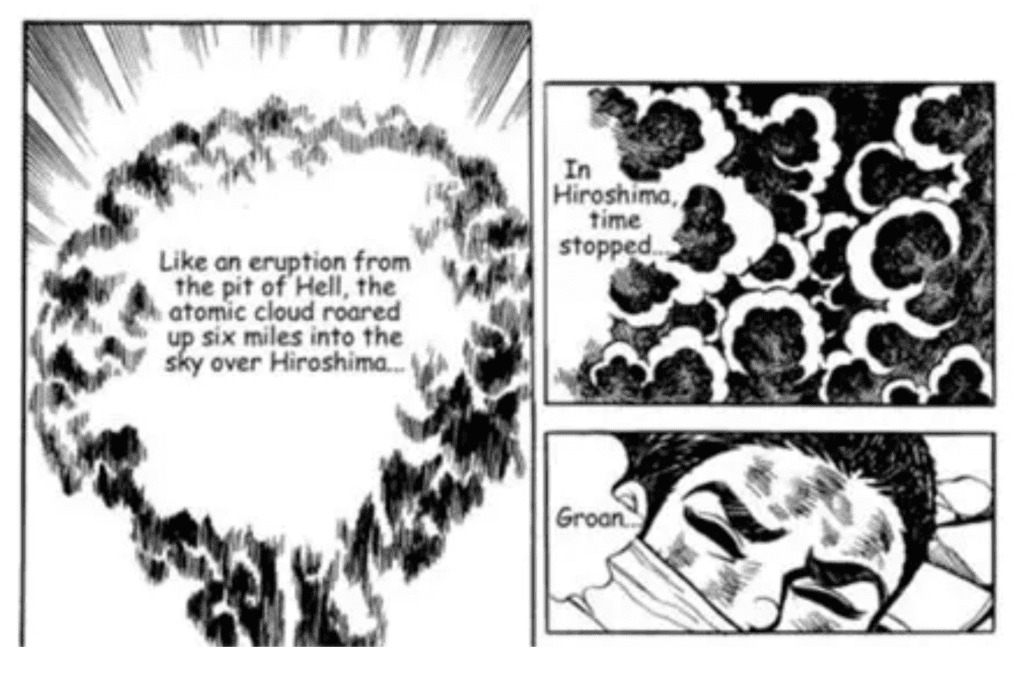

We will also read the first volume of hibakusha (atomic bombing survivor) Keiji Nakazawa’s Barefoot Gen (1973-1987), a semi-autobiographical account of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima. We will pair Barefoot Gen with an article on the systematic erasure of atomic survivors’ experiences in the postwar decades to underscore the historical value (and intergenerational popularity) of Nakazawa’s trauma narrative.

“Hibakusha share not only traumatic memories of the A-bomb explosion itself but also, and above all, a common identity as the ‘radiation-exposed,’ living with the reality and perpetual threat of delayed radiation effects. The feeling that they are carrying an ‘unexploded bomb’ inside their bodies has not abated over the decades, and despite scientific assertions that deny the existence of genetic effects . . . such fears extend to their children and to future generations.”2

Figure 1: From Barefoot Gen

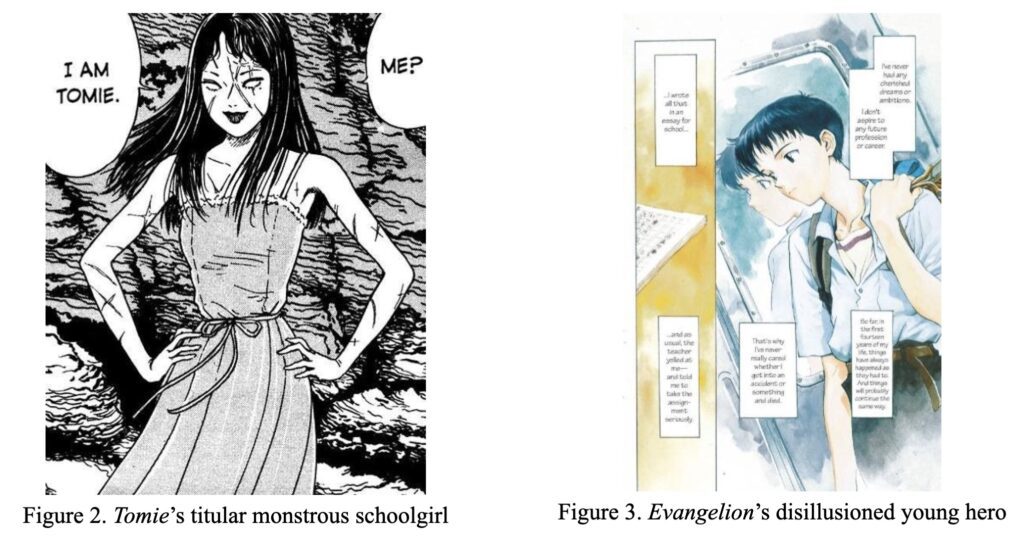

To provide a final example, contemporary Japan witnessed an accelerated fragmentation of conventional socio-cultural institutions ranging from the family to spirituality, the education system to the workforce. In this class, we will analyze some of the most pervasive pop cultural tropes to materialize (or re-materialize) in this context: for examples, the monstrous schoolgirl of J-horror and the teen boy-turned-high-tech hero of science fiction.

Throughout the semester, students will complete low-stakes assignments requiring them to craft short analyses of assigned manga with prompts to guide them. For examples:

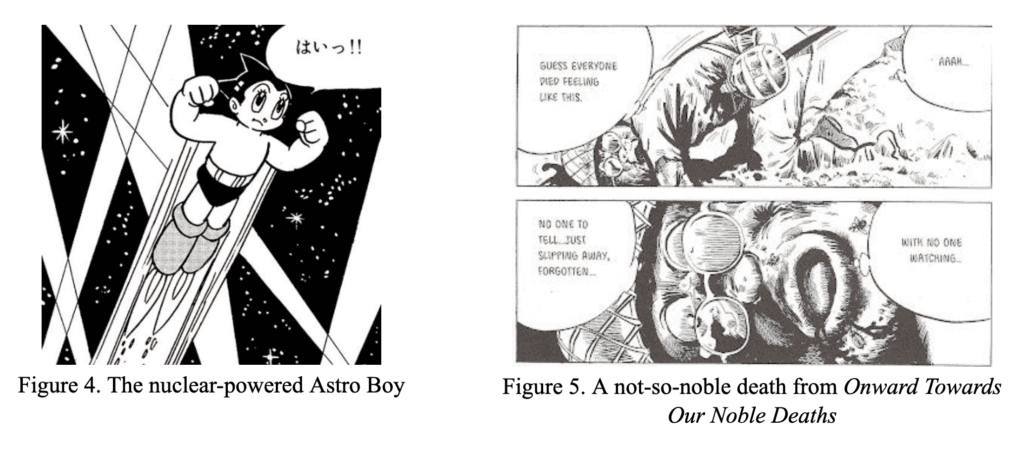

| Bring to class a ~250-word analysis of Astro Boy, with attention to how it seeks to divorce nuclear technology from the violence of the atomic bombs. In your analysis, provide close reading of at least one specific scene. | Bring to class a ~250-word analysis of Onward Towards Our Noble Deaths, with attention to how it portrays the realities of Japanese soldiers’ wartime experiences. In your analysis, provide close reading of at least one specific scene. |

In their higher-stakes midterm and final essays, students will put these analytical skills to work in more open-ended, comparative, and thorough contexts. For these essays, they will be asked to choose any three assigned manga and closely analyze them with attention to how they engage with a major Japanese historical theme (or interconnected themes) covered in class.

In the future, I might also experiment with different forms of assessment in this course. I am particularly interested in exploring assessments that, to borrow from my fellow comics course creator Dr. Gregory Daddis, “mirror the medium.” That said, even when using rubrics, in past courses I have found exclusively visual “creative” assignments challenging to fairly assess. I find myself inclined toward assigning a “visual essay” (for which the City University of New York provides clear, concise general guidance) in which students combine their own images and text to explore a course theme.

- John Dower, War Without Mercy: Race and Power in the Pacific War (New York: Pantheon, 1987), 229.

- Maya Todeschini, “Illegitimate Sufferers: A-Bomb Victims, Medical Science, and the Government,” Daedalus 128, no. 2 (1999): 67-100.

Raechel Dumas (Ph.D. in Japanese, University of Colorado at Boulder) is a specialist in modern Japan, with emphasis in the histories of literature and visual culture. She is especially interested in the gender and sexual politics of “dark” popular genres including horror, crime fiction, and science fiction. Her first book,The Monstrous-Feminine in Contemporary Japanese Popular Culture (Palgrave Macmillan, 2018), explores constructions of female monstrosity in Japanese fiction, manga, film, and video games produced from the 1980s through the new millennium. Articles by Dr. Dumas have appeared in multiple academic journals. She is working on her second book, Serial Affects, which examines gendered experiences and expressions of trauma in English-language streaming television series.