Written by

Michael Dominguez

San Diego State University

Way back in 2008, a friend and I, both of us men of color, both of us lifelong readers of comics, attended the premiere of the Robert Downy Jr.-led Ironman film. As we waited in line, we chatted about favorite comics—he reflecting on how drawn to the X-Men he had been, given the focus on outsider status, and I talking up the recent run of Jaime Reyes Blue Beetle comics following the DC Infinite Crisis event—both excited for the film. A few hours later, we would walk out with the same kind of conflicted feelings we both often had around comics, namely because of the way race, ethnicity, and culture played out in them.

Specifically, I remember this scene in that 2008 Ironman film where Tony Stark, in his newly designed suit, flies across the world to dispose of Stark Industries weapons being used by terrorists. At one point, the terrorists are holding hostages, and Stark uses his extensive arsenal and technology to pinpoint the aggressive, threatening, vaguely Islamic looking, brown terrorists, and dispatch of all of them easily, leaving the hostages unharmed. Later, he fires a projectile at a tank, and coolly walks aways, as it blows up moments later. He flies off, returning to his spacious, tech laden mansion in Malibu.

Tony Stark walks away from an exploding tank on his way back to Malibu, CA in Ironman (2008). Who was responsible for cleaning up this near-East village in the global south after Tony Stark “liberated” it by blowing a bunch of stuff (and people) up? It sure seems like it wasn’t Ironman…

But what of the brown, global south folks whose village he just launched a bunch of high explosives into? What of the broader political issues and post-colonial tensions and artificial, European-drawn borders that were inevitably the cause of whatever the hell was going on in this village to start with? Those aren’t Stark’s concern or responsibility, apparently.

Liked we’d both long felt with comics, we were conflicted, because, while we both appreciated the artistic qualities of the film (who knew it would launch a film franchise with 33 and counting films?), the whole thing was, ideologically-speaking, a celebration of coloniality and Orientalism—that it requires a strong White man, his militaristic intervention, and the righteous wisdom of the metaphoric “West” (i.e. the Western epistemic world) to stop all the backward, uncivilized brown folks in the global south from killing each other. And that he could do so with pinpoint accuracy—and White moral superiority–such that hostages were spared, and collateral damage was an afterthought. Once his task is done, Ironman leaves this xenophobic, Orientalist fever dream of a third world/global south village to clean itself (and all the Ironman-produced rubble) up. And while the film explores some threads about the ethics of arms sales, we never broach the original sin of the global politics of colonization, or how race and culture are wrapped up in them. But hey, at least the Stark Industries weapons are gone!

We left that theatre feeling the same way we’d both felt reading comics all our lives as folks of color: conflicted, but resigned; thrilled by the storytelling, but a little sad because of whose story it was, again, and who was incidental to, yet impacted by, the action. We watched, as we had read, knowing the phenotypically, culturally, we were firmly in that latter category.

And so as a comics fan, you wanted to enjoy the thrill and escapism of the ride, the cool gadgets, and fun action, but the coloniality of it all…the reality of knowing your BIPoC gente are more likely the collateral damage than the hero…well, that made it hard love.

These questions, of identity, power, post-colonial politics, and the inevitable contradictions within the ideologies that comics and comic media more broadly (because what else are we to make of the decades long Marvel-verse and DC’s twice attempted cinematic universe) raise around race, ethnicity, and culture, are what CCS 235 focus on.

Today, 500 years on from colonization and 60 years after the civil rights movement and legislation supposedly (that’s a very sarcastic supposedly) codified racial equality, issues and questions of race, racial identity, ethnicity, culture, and belonging arguably remain the most defining features of U.S. social experience. The active presence or absence of race in our lives—what we call racialization—carves out our identities and outlook in profound, and varied ways. Borders, drawn in our surprisingly recent colonial past, and who belongs on which side of them, dominate our headlines. How racialized cultural practices and trends are being taken up shape our tastes and popular culture. Waves of political pressures shape our perceptions of capital O- “Other” communities as pathological, exotic, or humanized. And the permissibility/ impermissibility of just being able to speak transparently about all these issues, the immanence of racial experience, is somehow, well into the 21st century, under threat.

This is all to say that race, racial identity, and racial and cultural experience loom large in our collective socio-political experiences and imaginations, whether we want them to or not. And confronting their malignancies requires taking time to learn about their histories, intricacies, and dynamics, and both the insidious ways things like coloniality still creep into our lives, and the exciting, dynamic ways communities of color have evolved and transformed their practices as acts of resistance and resilience. CCS 235, as a CSU Area F (ethnic studies) GE course, is committed to helping students explore some of these questions, because doing so—unpacking and confronting how race and racism live in our lives—is not, as some suggest, harmful or its own form of bias, but essential to humanizing on another, and eradicating these last lingering malignancies from our society. We heal from trauma by confronting it, not ignoring it.

But let’s get back to comics. Comics have always reflected a huge spectrum of social experience, imagination, and ideology. They speak and depict things about the way we think of the world, the way we see each other, and reveal both prevailing and subversive socio-cultural and socio-political attitudes around the time of their creation. And that means that necessarily, inevitably, speak to and comment on how race and racism are being seen and understood, challenged or upheld. And learning how to read comics with all this in mind, in such a way as to expose and make transparent the racial messages and ideologies that surround us, is an incredibly important skill for any of us.

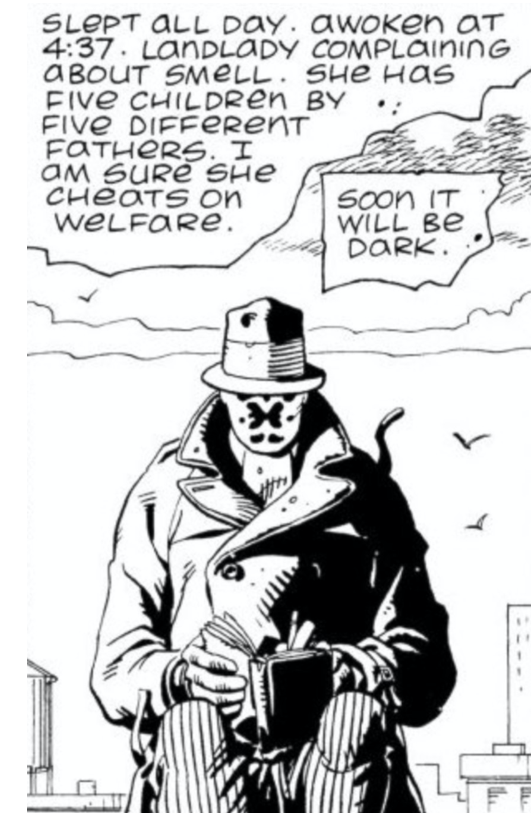

Take, for instance, Alan Moore’s Watchmen, one of the all-time classics of comic story-telling. A careful reading will reveal Moore’s incisive work to call attention to the colonial ideologies and toxicity that are wrapped up in the idea of “crime fighting” and the vigilante day dreams that comics represent—including the ways in which racialization and cultural pathologizing of those marginalized by neoliberal economics keeps that machine turning. Rorschach, in the text, is a straight up racist, driven by resentment for the slew of Others he muses about in his disturbing journal. The Comedian was a hyper-violent, patriarchal figure, fully embracing and reflecting American neo-colonialism, paternalism, and racialized nation-state militarism directed at the global south. Dr. Manhattan isn’t much better, it’s just that his racial politics are different, appearing in the intellectual alibis he creates for himself; he lives in a world of abstraction in which his responsibility doesn’t extend to the mundane, but very real, lived impacts of racism and racial experience.

Frames from Alan Moore’s Watchmen(1987)—there was no mistake about how he wanted us to see and understand these characters as flawed, problematic individuals…

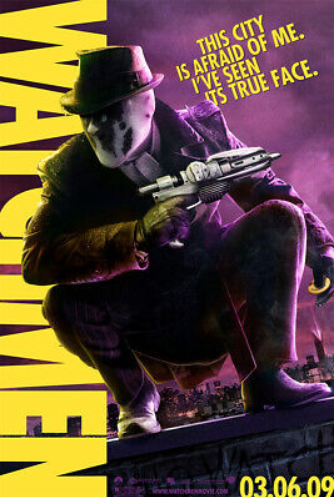

Some of this nuance was widely missed in the reading of Watchmen, much to Moore’s long-documented chagrin. And one of these folks who missed all that messaging was, clearly, Zach Snyder, because in the 2009 film adaptation, all the violence, heroism, and hyper-masculine bravado is preserved, but the ideological commentary on neoliberalism, nation-state violence, and criminalization is lost, and Rorschach, particularly, is transformed from racist sociopath into audience favorite and growling, rugged hero. Posters like this that promoted the film, pulling Rorschach’s quotes out of context—here, the quote “This city is afraid of me. I’ve seen it’s true face,” sounds all badass; in the text, this sentiment is wrapped up in obvious and off-putting racial resentment, showing the delusion behind this ethos of singular, infallible crime fighter—were oddly prescient to what the film itself would do: miss the point of the text in pretty profound ways. The comic and the film might as well be two different, unrelated properties, and that is, largely, down to how they understand and speak to race, racism, and other forms of social marginalization and pathologization.

A character poster promoting Zach Snyder’s Watchmen(2009) film. Snyder’s film interpretation of Moore’s graphic novel was both exactingly frame-accurate to the comic, and just as exactly inaccurate to its themes and ideas.

That’s why in CCS 235, I wanted to make sure we were able to explore some of these implicit messages about racial and cultural ideologies, the ways that work on us invisibly, and how they shake out across mediums and readings of texts, and interpretations of characters. Watchmen is a good example, one we talk about in the course—and the HBO Watchmen series, which wove itself into and around the history of the Tulsa Race Riots adds another wrinkle for conversation—but this kind of messaging abounds across comic media. Ideologies are all around us, as are race and differential racial experiences. When we start to read the word (or picture) more critically and clearly, we start to read the world more robustly as well, and doing so allows us to unlearn the racializing, colonial, ideologies that limit our capacity for humanity.

But none of that reflection on the presence of racial and colonial ideologies in comics is to say that those are the only things we find or can explore when we read comics. And in CCS 235, we also get the chance—like in any good ethnic studies course—to look at the dynamic ways in which race, ethnicity, and culture are being lived, transformed, and enacted in both the present and historical context.

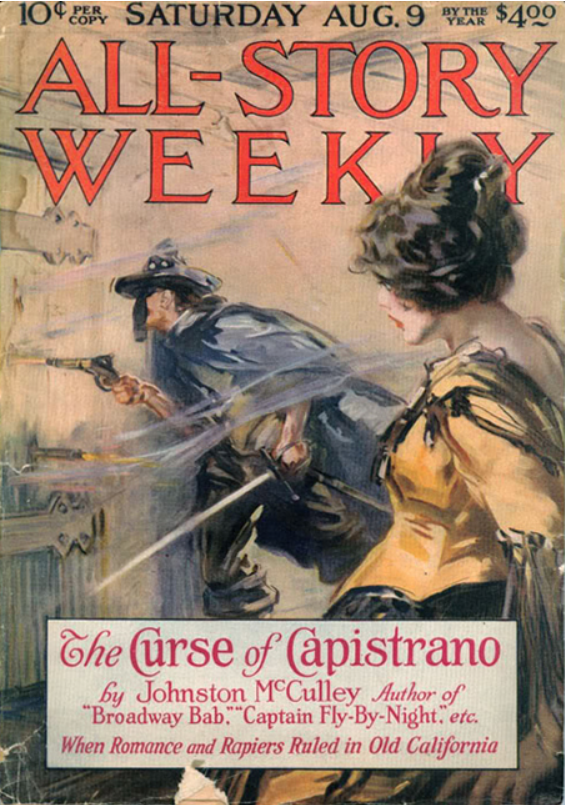

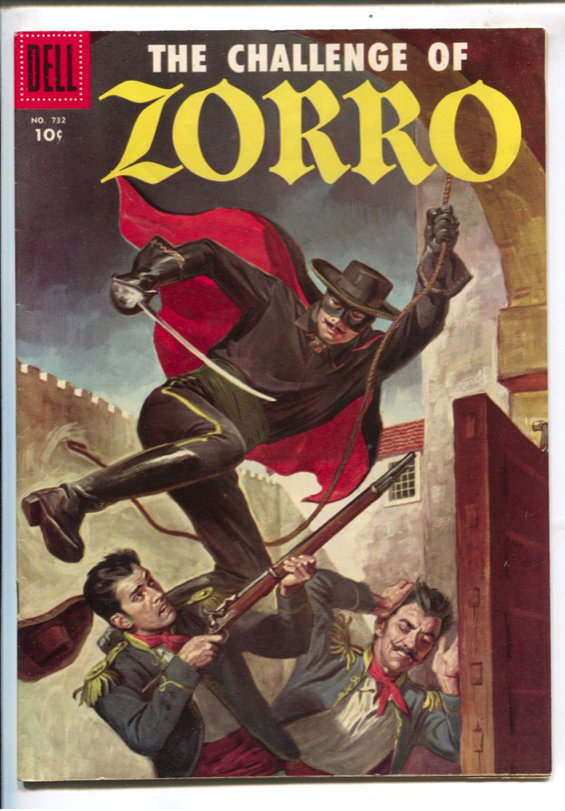

Like, who knew that the popular and well-known story of Zorro, immortalized in books and films and comics across a century plus, was inspired by the real-life exploits of one Joaquin Murrieta, a Mexicano who led a people’s revolt in response to the often violent seizure of land by Anglo-American settlers swarming into newly-annexed California in the late 1840’s and early 1850’s? I suspect not many of us. To the White American California government, Murrieta was a bandit and criminal. To the Mexicanos, he was a vigilante and freedom fighter (the first Chicano, some say, fighting back after the border crossed him). Either way, his story—heavily romanticized and fictionalized so that he was reimagined from Murrieta’s actual mestizo peasant rebel self into an old-money Hispano aristocrat with a soft spot for the poor, but a clear commitment to the status quo of socioeconomic hierarchy generally—became the origin for Zorro (who in turn would become the origin for Batman—who is originally and recurringly depicted as emerging from a screening of The Mark of Zorro on the night his parents are shot in Crime Alley—but that takes us into a different direction…).

The cover of the original Zorro serial (1919)—admittedly not exactly ideal representation, but a first step towards normalizing Latinidad in storytelling, all with a story based on the historical figure of Joaquin Murrieta….

Dell Comics’ run of Zorro in the early 20th century laid the foundations for the character as he is known today—and helped pave the way as an archetype upon which Batman and others were built. ¡Joaquin Murrieta presente!

And Zorro, despite his aristocratic bearing, politics of the status quo, and origin from the imagination and pen of a very White, very Anglo author (Johnston McCulley), represents one of the earliest positive representations of Latinidad in popular media, and a distinct contrast between other depictions of Mexicanos as vaguely uncivilized, lazy, savages, and the borderlands as lawless, empty frontier-land. In Zorro, the cultural complexities of the border received some serious play and attention. It might not have been all positive, it was a depiction of a place with relatable, attractive, and exciting culture that went beyond just the exotic (though, yeah, there was some of that too…and there’s SO much to talk about with the racial politics of Mexico and how Zorro storytelling has tended to portray that).

But it was storytelling like this as it appeared in serials, then comics and films, centering Latinidad, that makes Jaime Reyes and Blue Beetle become possible. We’ve now got a story where the action and narrative is set in the border-lands, where the hero is clearly a mestizo Mexicano, where the language of his internal monologue code-switches and uses Spanglish, and where the frontera, and Latinidad, seem to be just as substantial of characters themselves as any of the people populating the pages and frames.

Blue Beetle’s Jaime Reyes operates like a lot of U.S. Latinos—in Spanglish, and pulled back and forth across both real and metaphorical borders.

This kind of depiction of Latinidad manages to capture its dynamism and diversity. Blue Beetle books, and the recent film, normalize Latinx cultural practices, perspectives, and experiences, while also playing with the way that added perspectives (including, but not limited to, an extraterrestrial Scarab exoskeleton) bring those practices into conversation with shifting moral frameworks, evolving generational attitudes, and the politics of belonging that so many Latinx young people have to deal with. Blasted across comic pages and movie screens, Blue Beetle is a look at how Latinx folks are immanently crafting racial, ethnic, and cultural identity.

There are a lot of characters in DC Comic’s Blue Beetle, but the one that is perhaps most interesting is the border/frontera itself, and how it shows up in shaping the narrative.

These are just a few things we touch on, in just a few of the units, and that I wanted students to have the chance to explore, in CCS 235. Again, we can’t escape the way race and racial identity impact our world, shape our media, and live with us in social, material, and symbolic ways. Ignoring them; taking up a colorblind stance that pretends these things aren’t a part of our lives, does little but help the more malicious and insidious threads of resentment and bias thrive, and unfortunately, proliferate. By exploring how race and racism—and attitudes about them—are intentionally and unintentionally reflected in comic narratives, how creators are commenting upon and subverting them, and how BIPoC communities, writers, and artists are using comics to bring their dynamic stories to life, we are humanizing one another, understanding that racial experience matters, how it matters, and how we can see these aspects of our identity as significant, meaningful, and enriching to a world that is begging for empathy and perspective.

It’s been a minute since 2008, and even with all the tensions and contradictions, I’ve kept reading and watching comic media since that day at the movie theatre. Watching the ways that comics and comic media (and indeed the Marvel Universe that Ironman launched) grapple with our changing socio-political world, and the public and epistemic dilemmas that have arisen in our racial landscape and politics since then—around the U.S.//Mexico border, in the wake of George Floyd’s murder—have been fascinating. I’ve been both heartened and excited by things I’ve seen, and predictably dismayed by others. The epistemic space Blue Beetle carved out for Latinidad. the unflinching critique of coloniality that Black Panther’s Afro-futurism offered have been revelatory. But there’s also still been quite a bit of that traditional pathologization of the poor and melanated, and valorization of nation-state militarism and patriarchal racial and post-colonial politics that have always been present in comics.

Comics have always, and will always, continue to reflect our relationships with one another, and our relationships to how we are making sense of this impactful thing we know as race/racial identity. My hope is that CCS 235 will give folks an opportunity to see how they can read those things more transparently and meaningfully, both in the world around us, and on the pages and screens of the comic ecosystem. In so doing, we deconstruct the malignancies still living in our neo-colonial world just a little bit, and keep inching close to liberation and humanizaiton.

Michael Domínguez, Ph.D. is an Associate Professor in the Chicana/o Studies Department at San Diego State University. Previously a middle school teacher in Nevada (where he regularly used comics as part of his literacy and ESL curriculum), Dr. Domínguez’ teaching and research focuses on the affective experiences of historically marginalized youth, the possibilities and tensions of ethnic studies in K-12 schools, and how decolonial frameworks can transform teacher education praxis. As SDSU, he leads the Center for K-12 Ethnic Studies Education, and his current community-based partnerships include ethnic studies teacher support partnerships, and an ethnographic study of pedagogy in athletic spaces. His work has been published widely, and a co-authored book, Decolonizing Middle Grades Literacy, was released in 2023.