Written by

Dr. Elizabeth Ann Pollard, Professor of History

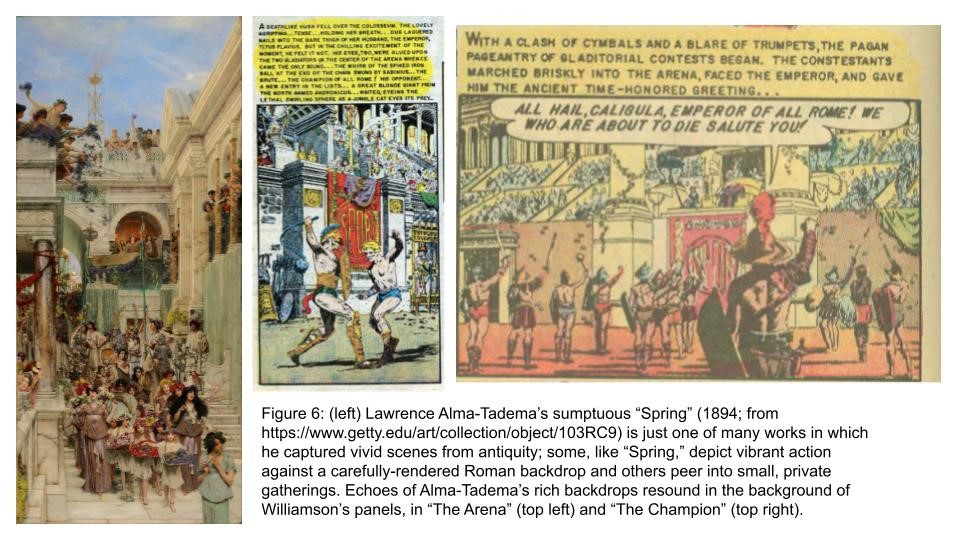

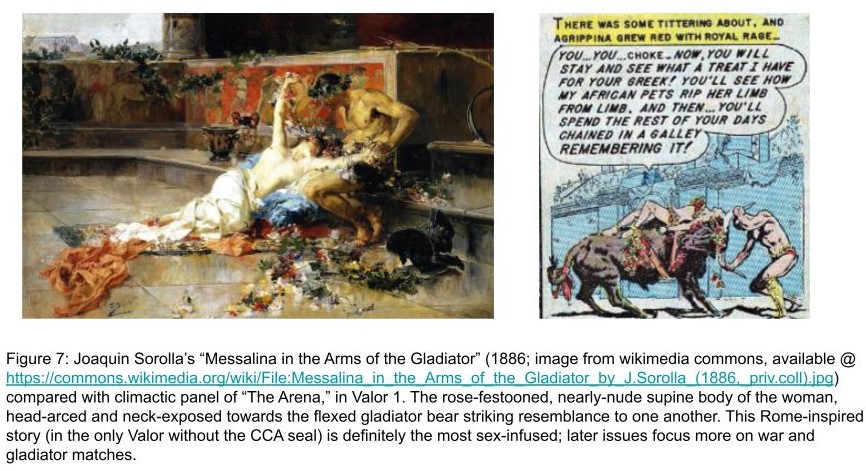

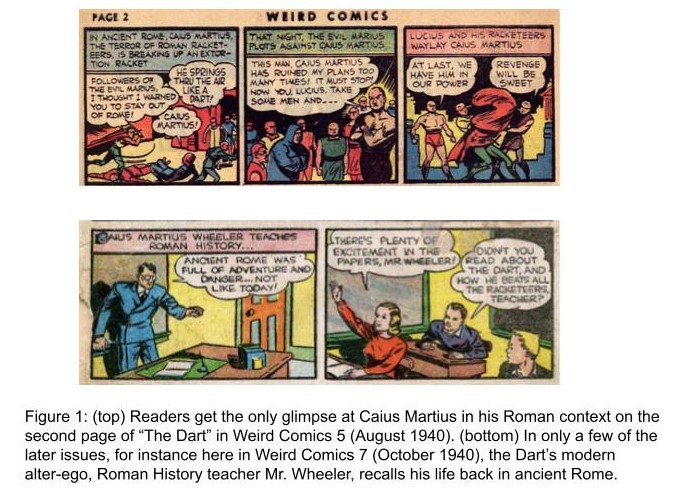

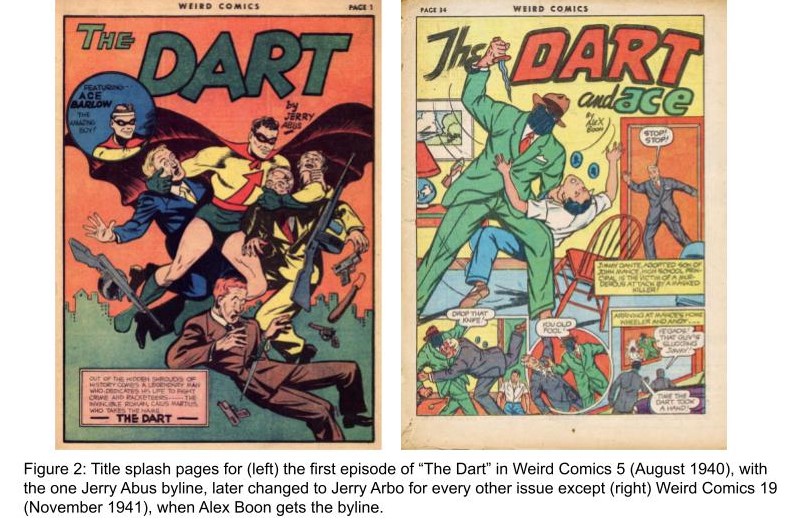

This past week brought the exciting opportunity to participate in a panel discussion on the history of animation — Cave Paintings to Comics: A Brief History of Animation — to accompany the new Animation Academy exhibit at the Comic-Con Museum in San Diego’s Balboa Park (see S.C. Bard’s coverage in “SDSU Experts to Discuss History of Animation at Comic-Con Museum,” SDSU NewsCenter 21 February 2023). Although I do not profess to be an expert on modern animation — beyond every ‘80s kid’s heavy dose of after-school Hanna-Barbera and in Saturday morning cartoons like the Flintstones, Scooby Doo, Justice League, and Smurfs — I have spent a lot of time thinking about how art from the distant past came alive for its viewers and the ways that artists long ago worked to breathe life into their creations. My research on women accused of witchcraft in the Roman world spurred my initial explorations of life-breathed-into-art and the relationship between representations and realities [E.A. Pollard, “Witch-crafting in Roman Literature and Art: New Thoughts on an Old Image,” Magic, Ritual, and Witchcraft Vol. 3, Issue 2 (Winter 2008), 119-155]. That professional background aside, my personal interest in the topic is, of course, indelibly marked by my own favorite animated characters … those powerful women who are infinitely more nuanced and compelling than the princess protagonists… namely the witches, from the hand-drawn animation of Art Babbitt’s Evil Queen in Snow White (Disney, 1937) and Marc Davis’s Maleficent in Sleeping Beauty (Disney, 1959) to the stop-motion (make that heart-stopping) Agatha Prenderghast in Paranorman (Laika, 2012). Professional and personal background aside, to prepare for this panel discussion I found myself reflecting on just how far back might the idea and principles of animation go?

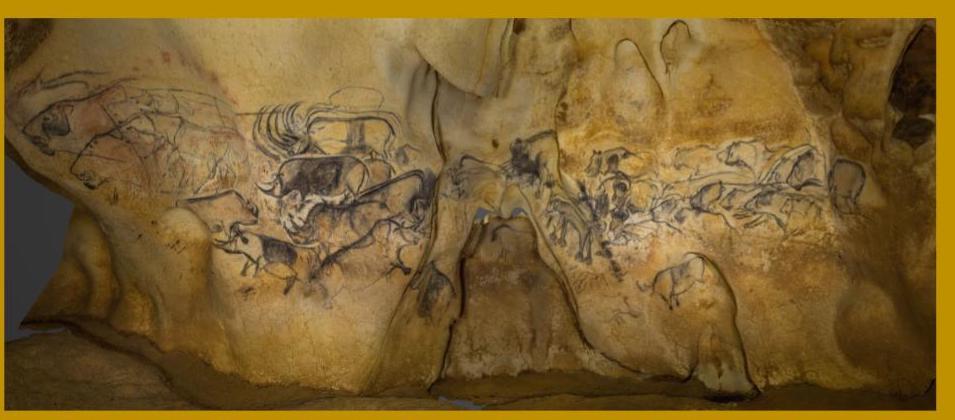

One might reasonably argue that animation is as old as art itself, beginning with cave paintings in the paleolithic era. Scholars have long puzzled over the purpose of the beautiful paintings on the walls of caves dating back to more than 30,000 years ago. Are these paintings somehow the religious devotion of shamans? Recollections of a successful hunt? The result of that very human urge to declare “I am/was here!”? Whatever their purpose, there’s no mistaking the accomplished artistry of these works. And, possibly, their status as the earliest animation. Take for instance, the lions and rhinos from Chauvet cave in France from 30,000-33,000 years ago (See Figure 2). Whoever painted this scene carefully overlaid lions (or one lion?) in slightly different poses, moving towards bison and rhinos who similarly are rendered as what look like multiple layered sketches of the same rhino with head and horn in slightly different position, as if running or nodding. The stroboscopic effect of a flickering, and possibly moving, torch — while someone, perhaps a shaman, told a story — would have brought these images to life for their subterranean spectators. Stroboscopic, or light-flickering, effects are key to the development of modern animation, in such devices as the zoetrope and phenakistiscope from the late 19th century. The same principles would have animated the layered images of animals on cave walls.

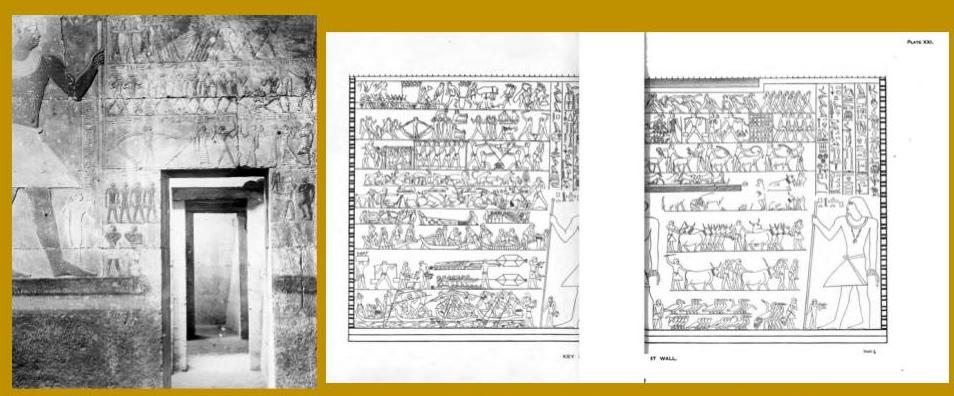

Note the progression of images on each register of the line drawing, for instance harvesting papyrus (top left) and wrestling (top right). To a viewer in ancient Egypt or to one pulling the image through a lantern slide three thousand years later these step-by-step progressions may well have produced an animated effect.

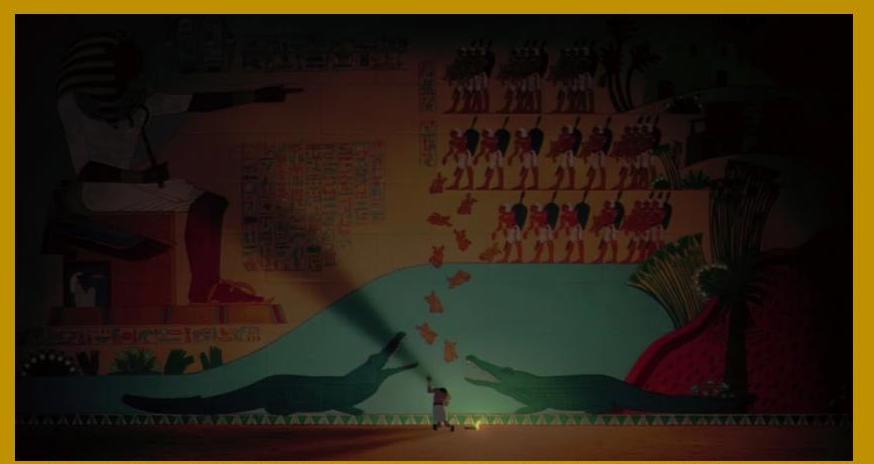

Other nods to a deep history for animation might be found in tomb paintings of ancient Egypt, such as the tombs of Mera (or Mereruka) and of Ptah Hotep, from Saqqara of the late third millennium BCE (See Figure 3). The registers on these tomb paintings show repeating images performing the same task/pose and/or images at slightly different stages of the same task, whether collecting papyrus stalks from a marsh or wrestling (among other activities). Whoever may have viewed these images or, as with the paleolithic images whatever their purpose, the sequence of images lends itself toward interpretation as an animated step-by-step scene beyond the narrative of sequential art, which tends to ask the reader to do more closure between panels. It’s almost as if one could place these images on a series of flipped pages and see the scene progress. What’s all the more fascinating and “meta” is that many of the images we have today of these ancient tomb paintings were captured on slides for viewing in magic lanterns which themselves hold a place in the more modern history of animation. If such slides were drawn across the viewer of the magic lantern, they may well have brought ancient Egypt to life for the ca. 1900 viewer, just at a time when Egyptomania was at its height and modern animation was in its infancy. To take the ancient Egyptian example even more “meta”, it’s quite striking that Dreamworks appears to have acknowledged modern animation’s debt to ancient Egyptian artistic aesthetics. The scene in Prince of Egypt (Dreamworks, 1998) in which Moses learns, through his torchlit viewing of Egyptian wall art, of the slaughter of Hebrew children demonstrates in animated form the way that such wall art may have been perceived as animation long ago. [Dreamworks once again paid homage to a different kind of ancient art’s influence on animation in Kung Fu Panda 2 (2011). The final credits consciously echo the style of East Asian and Southeast Asian shadow puppetry, yet another ancient art form that brought static images to life through manipulation of light and shadow. It’s worth noting that Laika’s Kubo and the Two Strings (2016) gives off some serious shadow puppetry vibes, as well.]

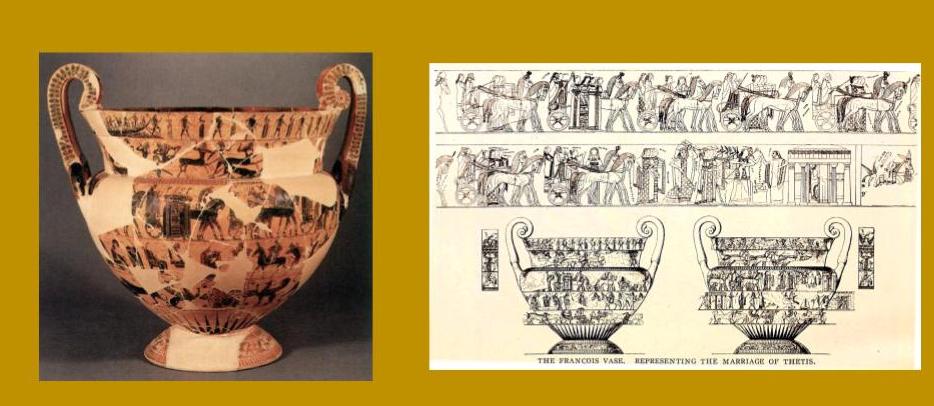

In addition to wall art from paleolithic to ancient Egypt (and, the repeated imagery one sees on such classical bas relief as the tribute bearers at Persepolis or on the Parthenon frieze from the fifth century BCE), arguably another type of ancient animation is the imagery on Greek vases. The showpiece François Vase from sixth-century BCE Etruria beautifully demonstrates the storytelling capacity of this medium. Participants at a gathering at which this piece may have been used for mixing and serving wine would have viewed (from top to bottom register): a boar hunt, the funeral games of Patroclus (Achilles dragging body of Hector), the wedding of Thetis and Peleus (with its who’s-the-fairest apple story that started the Trojan War), the ambush and killing of Troilus by Achilles, sphinxes and griffins, and pygmies and cranes. One could argue whether such vase painting is better interpreted as sequential art (more like a comic) or animation (of the repeating type, as described already, in Egyptian, Persian, and Greek wall art). Nonetheless, the Panoply Vase Animation Project has demonstrated the ways that modern animation can bring the stories on these vases to life for modern viewers; with Greek music playing in the background, the project animates the stories on Greek vases showing the action that is implied in the otherwise static images. Such modern animation of ancient vase art provides an imaginative illustration of how vase images might have come to life in the eyes of those who viewed them in antiquity by the flickering firelight of a wine-lubricated symposium.

A final example of ancient animation comes in the form of statuary; in particular, statuary that captures the moment of a transformation. Greek and Roman classical texts record a range of shocking transformations … for example, Callisto transformed into a bear to escape a rapacious pursuer (Ovid, Metamorphoses II.401-ff) or Pygmalion’s statue come to life (Ovid, Metamorphoses X.243-ff). [Side note: Interestingly, Encyclopedia Britannica lists Pygmalion as the legendary first animator for this act of creation (https://www.britannica.com/art/animation).] While statues of these transformational moments existed in antiquity, the 17th-century Bernini sculpture of Daphne’s transformation offers a great example of how a moment captured in stone can embody action in a way that makes it seem almost alive. As a viewer circles Bernini’s statue, what looks like Daphne’s hair and upwards reaching arms become bark and branch of the laurel tree into which she has been transformed. The scene in stone comes alive, in all its action and pathos. Interpreting scenes of transformation captured in stone as a kind of animation might seem a stretch were it not for the reportage of the imaginative second-century writer Apuleius, whose own Metamorphoses (or Golden Ass) tells a magical story of a man transformed into a donkey and then returned to male form through the grace of Isis. Apuleius’s novel recounts the visit of his lead character Lucius to the house of a witch. Apuleius describes the city in which the house Lucius is visiting as a place where it seemed “everything had been transformed by some dreadful incantation” such that “soon the statues and images would start to walk” (Apuleius, Golden Ass, Book II.1-5; A.S. Kline’s 2013 translation of the passage available here). In this passage, Apuleius describes a statue group in which the mythological character Actaeon is depicted at the moment when he is transformed into a stag to be devoured by Artemis’s dogs. Apuleius writes that the statue was so naturalistic that if the viewer gazed into the reflecting pool in which the statue was located, the viewer would have seen in the water’s reflection a “quality of movement.” Whatever one thinks of Apuleius’s story about witches and transformations, he gives modern readers an idea of how an ancient viewer might have seen a statue rendered in the shimmer of a reflecting pool as a kind of animation.

Animation… the Latin etymology of the word conjures up the idea of the animus, a breath of life infused into an otherwise inanimate object. Taking the time to muse on a deep history of animation breathed life into the topic for me. Torchlit images in paleolithic caves or Egyptian tombs … or even the vases viewed through wine-goggled eyes of symposium attendees or statues observed in rippling reflective waters by fiction authors with overactive imaginations … none of these had the huge audience of twentieth-century and later animation. Nonetheless, these examples do suggest a long history of artists making images and stories come alive.

Elizabeth Pollard is Distinguished Professor for Teaching Excellence at San Diego State University, where she has taught Roman History, World History, and witchcraft studies since 2002. She co-directs SDSU’s Center for Comics Studies and recently debuted a Comics and History course exploring sequential art from the paleolithic to today. Pollard is currently working on two comics-related projects: an analysis of comics about ancient Rome over the last century and a graphic history exploring the influence of classical understandings of witchcraft on their representations in modern comics. Pollard has co-authored a world history survey (Worlds Together, Worlds Apart) and has published on various pedagogical and digital history topics, including DH approaches to visualizing Roman History.