Written by

Dr. Elizabeth Pollard, Professor of History

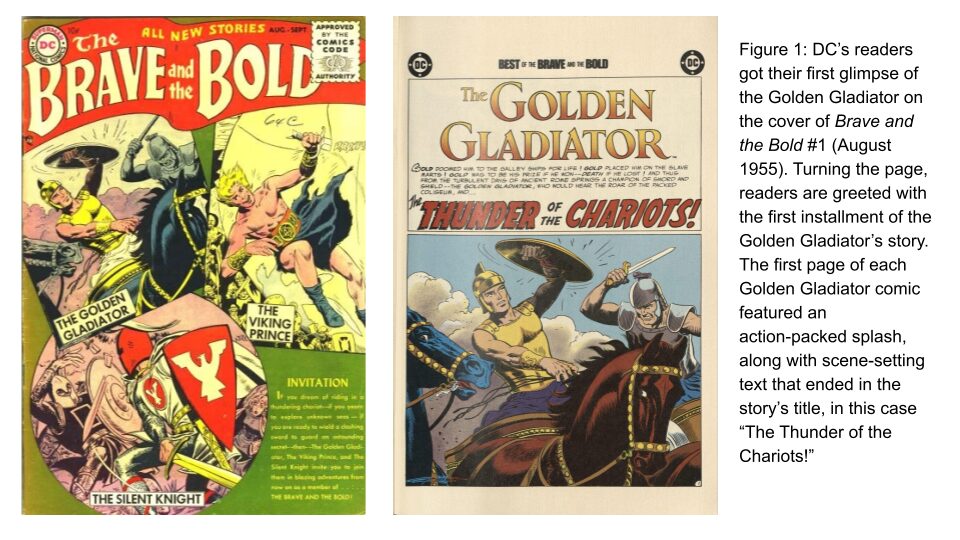

Every other month from April to December 1955, EC’s Valor transported readers to ancient Rome — as well as other historical periods, including medieval Europe, the Haitian Revolution, twelfth-century BCE China, and Kublai Khan’s Mongol empire — for one-shot stories of gladiatorial combat, veteran soldiers, and imperial intrigue (See Post-Code EC Goes to Ancient Rome). EC’s Al Williamson, Angelo Torres, Joe Orlando, and Wally Wood had found a pseudo-historical formula that worked, and rival publisher DC appears to have recognized a good thing when they saw it. By August 1955, DC’s own foray into “historical” heroism debuted… Brave and the Bold. Just as the cover of Valor #1 had announced EC’s “new direction” with an explanation in the editorial Round Table on the comic’s first page, DC issued an “invitation” on the cover of its first issue: “If you dream of riding in a thundering chariot — if you yearn to explore unknown seas — if you are willing to wield a clashing sword to guard an astounding secret – then The Golden Gladiator, The Viking Prince, and the Silent Knight invite you to join them in blazing adventures from now on as a member of — THE BRAVE AND THE BOLD!” Instead of the one-shot stories of Valor, DC would explore individual heroes across multiple issues. And for its Roman-era comic, readers followed the adventures of a captured shepherd, turned enslaved gladiator, and eventually freed protector of children, women, and even Rome, itself: Marcus Tiberius, the Golden Gladiator.

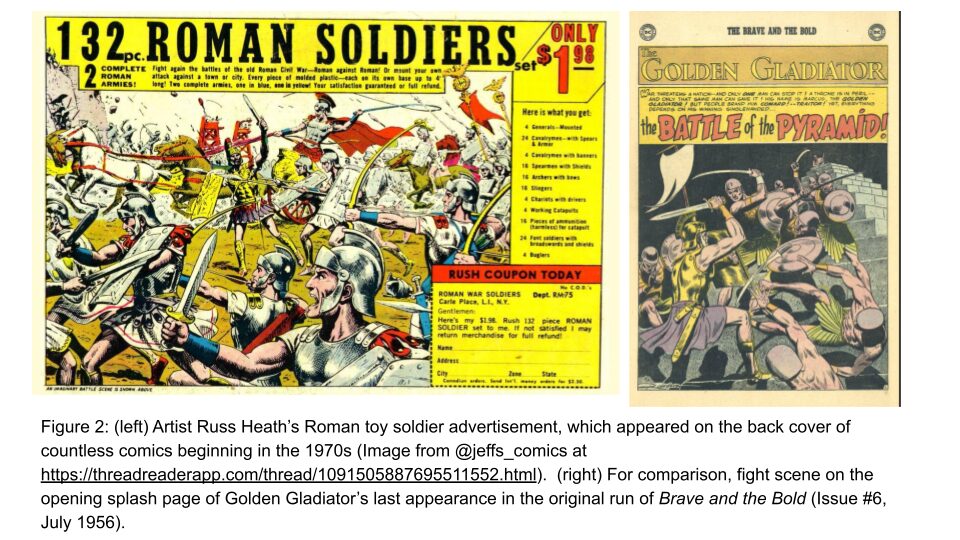

Across the five issues of Brave and the Bold that featured Golden Gladiator (GG) stories in 1955/56, the creative team was headed up by Bill Finger (writer), Russ Heath (art), and Petra Scotese (colorist). Bill Finger was a legendary DC writer, whose role in co-creating Batman with Bob Kane was officially recognized only very recently (Bill Finger on ComicVine). DC database lists Ed Herron, a prolific writer on such titles as Batman, Superman, and patriotic Star-Spangled War Stories, as a sometime writer for GG (https://dc.fandom.com/wiki/The_Brave_and_the_Bold_Vol_1_1); but Herron does not appear on the by-line on the first page of of any of the GG comics. Artist Russ Heath was particularly well-known for his war comics, westerns, and romance, all three of which genres resonate in the GG stories. Later in his career, Russ Heath drew toy-soldier advertisements that appeared on the back of many comics (https://www.lambiek.net/artists/h/heath_russ.htm). Heath’s advertisement for the 132-piece Roman soldier set is a fury of Roman soldiers, wielding their gladii, shooting arrows, riding in war chariots, galloping on horseback, assaulting a fortified position… with the caption “imaginary battle scene is shown above” (For more on the full range of these plastic soldier ads, see Feb 1, 2019 thread by @jeffs_comics at https://threadreaderapp.com/thread/1091505887695511552.html). Petra Scotese (aka Goldberg) was a colorist for a wide range of Marvel comics in the 1970s and 80s. According to WorldCat she’s credited with “145 works in 179 publications” including Wanda and Vision, X-Men, and George Perez’s Wonder Woman. In Finger, Heath, and Scotese, DC was clearly throwing some of their most impressive talent at the Roman hero in DC’s pseudo-historical Brave and the Bold.

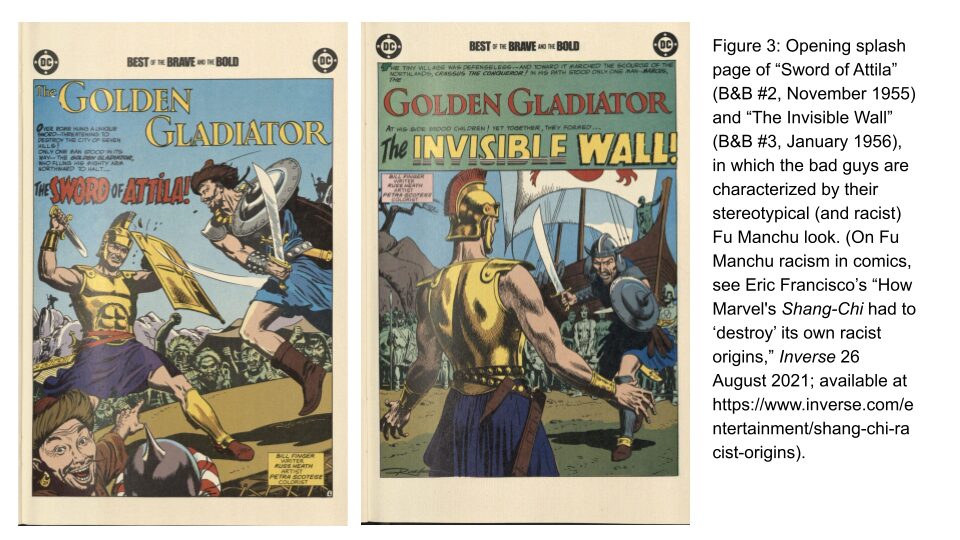

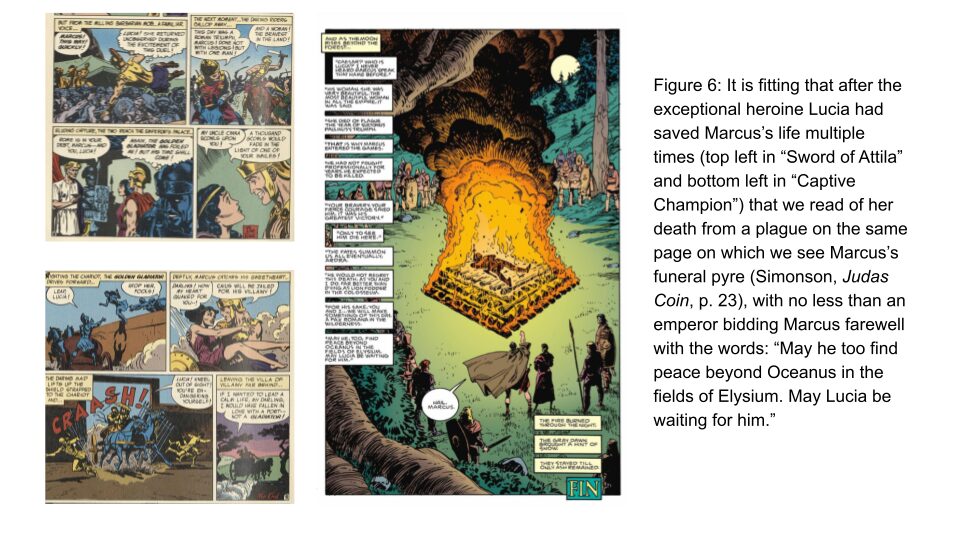

Although Brave and the Bold ostensibly followed the storyline of a single hero, Golden Gladiator’s storyline is a bit jumbled, riddled with what appear to be continuity errors and ahistorical elements. Readers meet Marcus in “Thunder of the Chariots” (B&B #1, August 1955) as a young shepherd who is kidnapped by a soldier named Cinna to serve as a patsy for an assassination plot. Condemned to row in the galleys, Marcus saves his fellow enslaved rowers from a Nubian lion bound for the arena in Rome. Marcus ends up in the arena, where he catches the eye of Cinna’s niece Lucia. Marcus fights a bull and races in a chariot race to win his freedom and become “The Golden Gladiator.” In the next installment, “The Sword of Attila,” (B&B #2, November 1955), Cinna nominates Marcus to sneak into “Hunland” and steal the titular sword. Cinna’s niece Lucia sneaks out of Rome to help Marcus on his quest. Marcus ends up in one-on-one combat with Attila, during which Lucia provides the distraction that allows both of them to escape with Attila’s sword. “The Invisible Wall” (B&B #3, January 1956) pits Marcus, no Lucia in sight, against “Crassus the Conqueror,” in a storyline befitting an old western: frontier town filled with women, children, and old men who use their wit, a toy ship and a goat army to stave off attack. Lucia returns in “Captive Champion” (B&B #4, March 1956), where our Golden Gladiator appears inexplicably to be back in the arena, with the evil Cinna suggesting he belongs in the golden menagerie of a collector named Gaius. Lucia helps Marcus escape, and in the comic’s last panel she proclaims: “If I wanted to lead a calm life, my darling, I would have fallen in love with a poet, not a gladiator!” But, in the last appearance of Golden Gladiator in the 1950s, “The Battle of the Pyramid” (B&B #6, July 1956), Lucia is gone (no explanation) and Marcus helps the “Nile Queen” keep the peace with the desert tribes by foiling her prime minister’s plot to cause war. The appearance (and disappearance) of Lucia, as well as Marcus in the arena, out, and then back in again … these apparent inconsistencies would have made it challenging for a reader who was attempting to follow a coherent story-arc for Marcus.

Writer Bill Finger does not appear to have much concern for historicity. A few examples suffice to illustrate this point. Finger names two of the “bad-guys” Cinna and Crassus, appellations evocative of villains (depending on one’s chosen side in the civil wars of the first century BCE). From at least the fourth century BCE onward, Rome had faced threats from the north (first Gauls and then later Germanic peoples), so the story line of “Invisible Wall” feels at least a little believable. But then, the threat faced is a band led by a very Roman-sounding Crassus who, along with his troops, is dressed in wildly inaccurate garb (a strange combination of vaguely Norse, vaguely Saracen, but definitely “other”-looking gear). Similarly, an unnamed but very Cleopatra-like “Nile Queen” (B&B #6) would seem to indicate a first century BCE context. But “Sword of Attila” (B&B #2) had Marcus going toe-to-toe with Attila himself, leader of the Huns in the mid-fifth century CE. While Finger and Heath were creating a comic and not a history book, it’s clear that historical accuracy and even basic chronology were of little importance to them in telling Marcus’s story. More likely they were building a character and storylines consistent with the 1950s zeitgeist: continued suspicion of Germanic/Hunnic peoples post WWII and even Nasser’s nationalization of the Suez Canal in July 1956, the same month as “Battle of the Pyramid” came out!

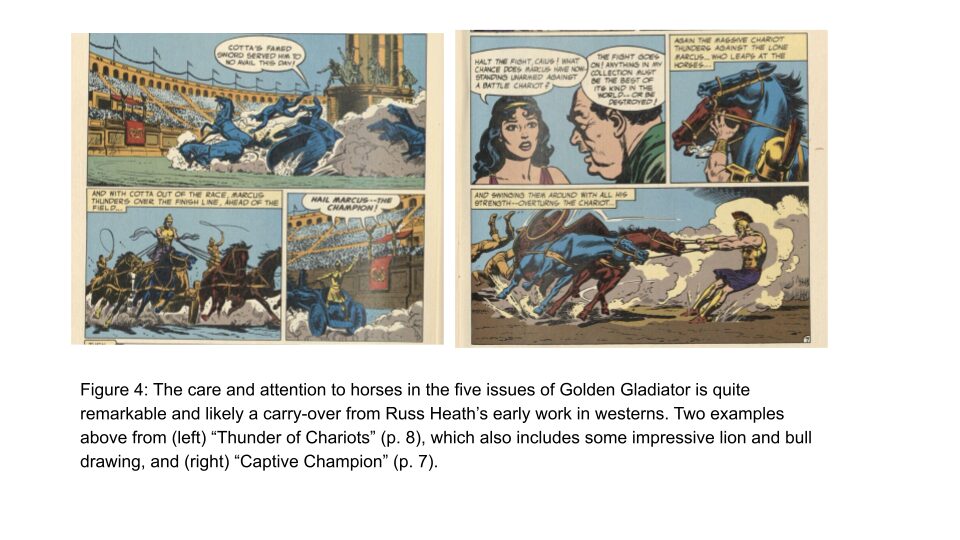

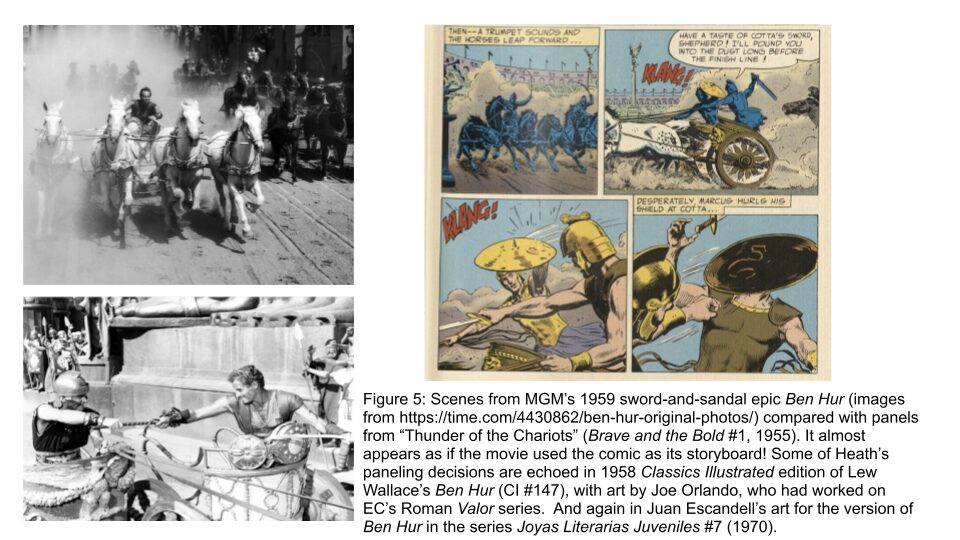

As for the “look” of the comic, each begins with a first page splash that sets the stage. Subsequent pages feature irregular-sized paneling, although the comic reads mostly left to right, top to bottom. Narrative text-boxes drive the story and word balloons distinguish spoken dialogue and exclamation (encapsulated by a solid line, with nearly every line punctuated by an exclamation point!) from internal dialogue/thoughts (cloud-like appearance). There are plenty of motion lines for the swash-buckling action of punching, sword-slashing, and even pole-vaulting onto a ship that has left port. And the pages ring with fight scene onomatopoeia (snap, crack, klang, clatter, swish, r-rumble, crash, and sprong). Also noteworthy is the attention to horses throughout, which is likely due to Heath’s early work in western comics in the 1940s. And the intertextuality does not end there. While EC’s Valor was in dialogue with the sword-and-sandal epics of its day, DC’s Golden Gladiator appears to have influenced contemporary imaginings of chariot racing. Predating MGM’s Ben Hur by several years, scenes from the movie appear to have used Heath’s vivid imagery almost as storyboards for the film; and the film’s imagery is echoed in later comic versions, including Joe Orlando’s art in Classics Illustrated (#147, in 1958) and that of Juan Escandell in Joyas Literarias Juveniles (#7, in 1970).

After his appearance in “The Battle of the Pyramid” (B&B #6, July 1956), Golden Gladiator unceremoniously disappears from the pages of Brave and the Bold, a series which continues for decades and ultimately introduces such greats as the Suicide Squad (B&B #25, 1959) and the Justice League of America (B&B #28, 1960), among many other DC legends. In Brave and the Bold #7 (September 1956), Finger and Heath began collaborating on a different hero, Robin Hood, who replaced Golden Gladiator in the cycle of heroes whose adventures B&B followed. The next appearance of Marcus is quite recent: Walter Simonson’s The Judas Coin (DC Comics, 2012). Simonson’s graphic novel uses the unlucky shekel from the purse paid to the cursed betrayer of Jesus to weave together a story that includes Brave and the Bold heroes old and new, from Golden Gladiator, to the Viking Prince, to Batman and beyond. Simonson’s treatment settles the questions of temporal context (placing Marcus firmly in the first century CE, as a veteran wandering the frontier with emperor Vespasian) and what ultimately happened to Lucia and Marcus. Lucia, whose bravery had more than once saved Marcus, has died from a plague. And Marcus, the valiant Golden Gladiator, meets his end diving to stop a would-be assassin’s knife throw from killing Vespasian. From the reader’s first meeting of Marcus as a young sheherd accused of an assassination plot, to a grizzled old veteran who foils one, the Golden Gladiator’s story comes to a fitting conclusion.

Note of thanks: Early Brave and the Bold comics are not easy to find. Many thanks to Pamela Jackson (SDSU Library, Comic Arts Curator), as well as Shawn Gilmore and Anna Peppard (both of whom answered a shot-in-the-dark cry for help in finding B&B #6), for their help in piecing together the Golden Gladiator run.

Elizabeth Pollard is Distinguished Professor for Teaching Excellence at San Diego State University, where she has taught Roman History, World History, and witchcraft studies since 2002. She co-directs SDSU’s Center for Comics Studies and recently debuted a Comics and History course exploring sequential art from the paleolithic to today. Pollard is currently working on two comics-related projects: an analysis of comics about ancient Rome over the last century and a graphic history exploring the influence of classical understandings of witchcraft on their representations in modern comics. Pollard has co-authored a world history survey (Worlds Together, Worlds Apart) and has published on various pedagogical and digital history topics, including DH approaches to visualizing Roman History.