Written by

Ben Jenkins, Lecturer, Rhetoric and Writing Studies

San Diego State University

Normally, when I tell my colleagues about the plan for one of my courses, I quickly see their faces drop as they realize that they’re stuck listening to me talk about rhetorical analysis. They’ll usually give me at least a few “that’s really interesting” comments with a nod of the head before they quickly remember that they urgently need to grade some papers or give blood.

But ever since I started telling them about my new course, The Rhetoric of Comics, I see genuine excitement overcome their whole body. They become animated as they forget to ask me about the research and pedagogy and instead focus on their own favorite comics. I’ve had discussions with people about Batman, their favorite manga titles and other works they’ve enjoyed since they were kids. Those discussions usually circle back to a question like “do you think I’d be able to use comics in my course?” It’s at this point that I direct them to the work being done at Comics at SDSU. As part of the NEH Comics and Social Justice Grant awarded to Comics at SDSU, I was able to create a course centered on the rhetoric of comics that allows students to understand the rhetoric used in comics, how that rhetoric helps or hinders marginalized voices, and allows students to practice what they’ve learned as they work on creating their own comic.

Throughout the process of developing this course, I kept trying to recall what I would have wanted to study in a rhetoric of comics course as an undergrad; the development of the three main projects was the key to everything.

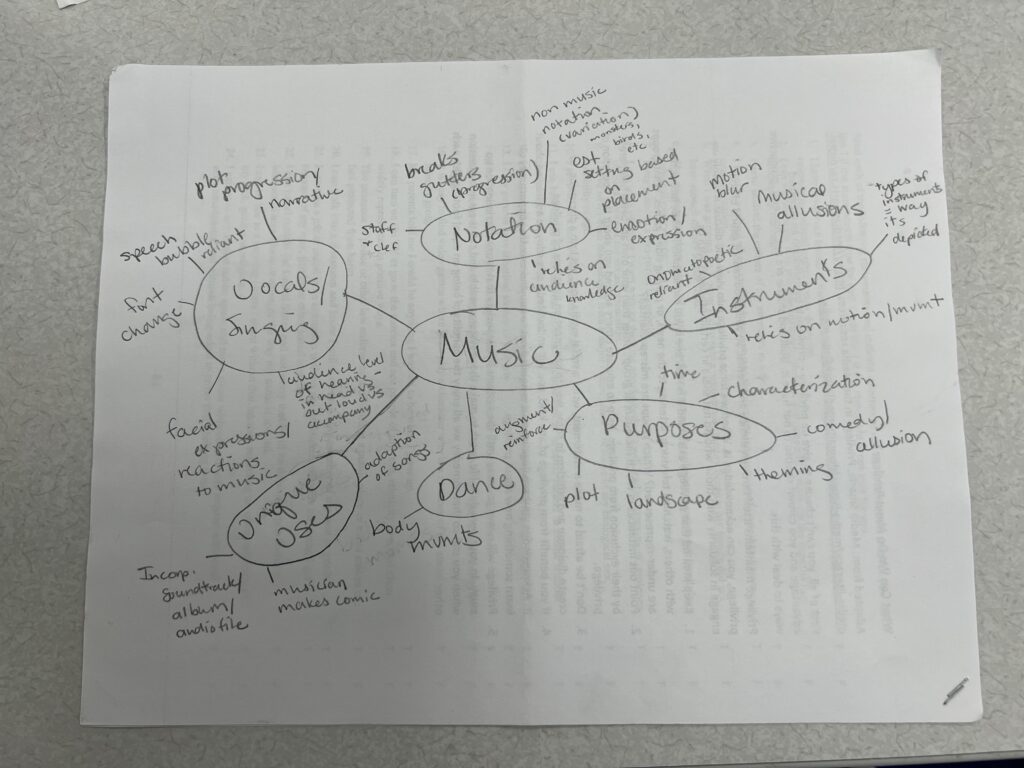

With the first project, I centered the focus on exposing students to the visual rhetoric present in comics, and how the medium allows for a level of communication that isn’t possible in film, books, or audio. I developed lesson plans ranging from interpreting color, to general introductions to the concepts of visual rhetoric and sequential art.

Part of the fun of creating this class was coming up with a reading list. The main textbook I chose to use was Scott McCloud’s Making Comics (2006). While the content has some information he covers in his previous book, Understanding Comics (1993), it also contains helpful information on the developmental aspects of creating a comic book. By utilizing the information from McCloud and other scholars, I was able to create lessons that highlight the many rhetorical and creative decisions comics creators make throughout the process.

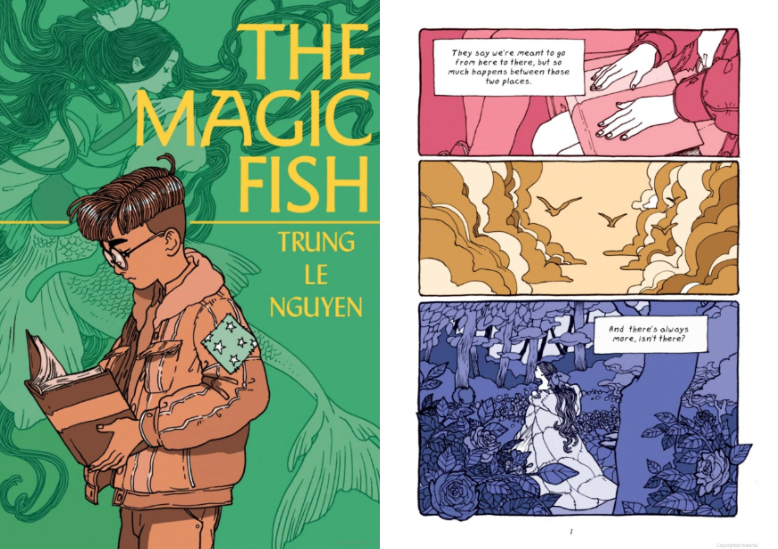

While I chose a number of comics to highlight as examples of storytelling and technique, the main comic I focused on was The Magic Fish (2020) by Trung Le Nguyen. Nguyen’s limited use of three color palettes paired with three different storylines helps clarify the difference and meaning of each path. With Nguyen’s beautiful work, and with McCloud’s technical explanations, I was able to create lessons that help students see how comic storytelling creates a world for the reader that doesn’t compare to other mediums.

The second project was created with social justice and marginalized communities in mind. For this project I ask students to compose a multimodal essay, comic, or presentation based on their analysis and comparison of two comics that are either about a marginalized community, or feature a main character from a marginalized community. By comparing comics featuring marginalized communities student’s are able to recognize how assumptions and stereotypes play a role in the creation of some comics, and the interpretation of characters by some readers.

Finally in the third major project, I ask students to build upon what they learned as they created a comic of their own. I don’t expect the students to be expert artists, but I do want them to use the visual rhetorical strategies they’ve learned about in McCloud’s text, and to mimic storytelling and artistic techniques they might have seen in The Magic Fish and other comics. Just like Nguyen was able to tell his own story detailing what it was like to come out to his friends and family, I encourage students to tell their own individual stories through the comic medium.

Comics aren’t something one necessarily expects to encounter in a university setting, but they’d be wrong. Comics have been a part of our society for…well, I don’t actually know how long. I’m not a historian, but if you’d like to learn more about the history of comics, we have a course for that here at SDSU, and now we have a rhetorical analysis course on comics as well. It’s been a privilege to be able to create this class. My only hope is that the students who take the course learn to love and appreciate comics as much as I do.

Ben Jenkins completed his MFA in creative writing and his BA in English at SDSU. Currently, he works as a lecturer at SDSU while also teaching English at Miramar College. Ben is a tribal member of the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma. In 2016, he won the new voices Native American writing contest at the literary journal, See the Elephant.

Some of Ben’s interests include: literature and issues pertaining to American Indians and other indigenous people throughout the world, civil discourse, our relationship with technology, social justice, the environment, visual rhetoric, and comics.