Dr. Noah Arceneaux is a professor in SDSU’s School of Journalism and Media Studies and a big fan of comics! Check out his latest video about his personal collection of Radio Shack Comics! Please Enjoy!

Month: November 2022

Written by Gregory A. Daddis, USS Midway Chair in Modern U.S. Military History, San Diego State University

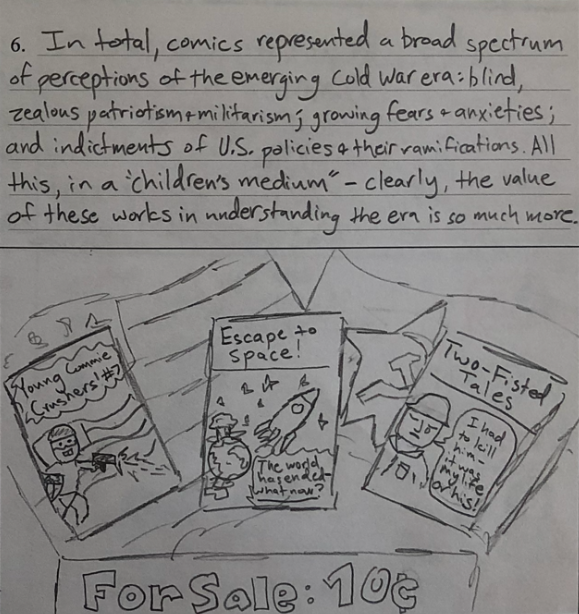

Teaching a Cold War comics course for the first time has reinforced what I have suspected for a long time—comics are some of the most insightful cultural products of post-World War II era.

Cold War era comics spoke to fundamental issues of American identity in a rapidly changing postwar society. They illustrated the fears that drove domestic and foreign policies at a time when evil, godless communists seemed lurking behind every dark corner. They expressed anxieties over living in the atomic era, when the possibility of nuclear Armageddon appeared ever more likely each time children ducked and covered under their school desks. And they reflected the possibilities and limits of achieving true social justice when many Americans’ civil rights were being contested by defenders of a stratified prewar status quo.

These representations of Cold War American society informed my course design for HIST 580, “Comics and Cold War America,” taught in the 2022 fall semester at San Diego State University. The course supported a National Endowment for the Humanities grant, “Building a Comics and Social Justice Curriculum,” co-directed by Elizabeth Pollard and Pamela Jackson, both of whom also lead our university’s Center for Comics Studies.

How comics, as cultural products, influenced Americans’ understanding of social justice issues helped shape the fundamental objectives that I hoped my students and I would achieve by course end. Though our study of comics, I sought ways in which we might be better equipped to articulate the domestic impact of the Cold War in the United States and the ways in which this global contest affected American citizens’ conceptions of culture, society, and social justice. And I hoped that our critical engagement with comics as Cold War cultural products would help us evaluate how they communicated the relationship between word and image.

But how to assess student performance and progress while trying to achieve two course objectives simultaneously—evaluating Cold War American society and culture while also engaging with comics as visual cultural products?

The answer, for me at least, was to mirror the medium.

For my mid-term exam, I provided my students with what I thought was an innovative prompt that would allow them to be more creative than simply writing a traditional essay:

“You have been asked by the editor of the Journal of Comics and Culture to develop a pictorial storyboard for a new feature titled “The Cold War at Home and Abroad.” The editor would like you to explain to the journal’s readership how Cold War comics demonstrated a close relationship between US foreign and domestic policies from 1945 to 1965. To do so, develop your story based on the readings from the first half of our course.”

I then offered them instructions for how to complete the exam:

“You must create your storyboard in six successive panels, an example of which is seen below. The top half of the panel should be used for a written narrative while the bottom half should be used for graphic illustrations. Be creative but remember to focus on making an argument and supporting that argument with historical content and analysis. As each panel’s written portion should comprise a full paragraph, ensure you write using complete sentences. Your drawings should support or enhance your written narrative. Manage your time wisely. Have fun.”

Along with the prompt and exam instructions, I attached an 11×17 paper that had six panels—two rows of three columns—laid out consecutively as a reader might see in a comic.

The results showcased how students not only were capable of evaluating Cold War comics on their own merits, but also of expressing their ideas in both written and visual form.

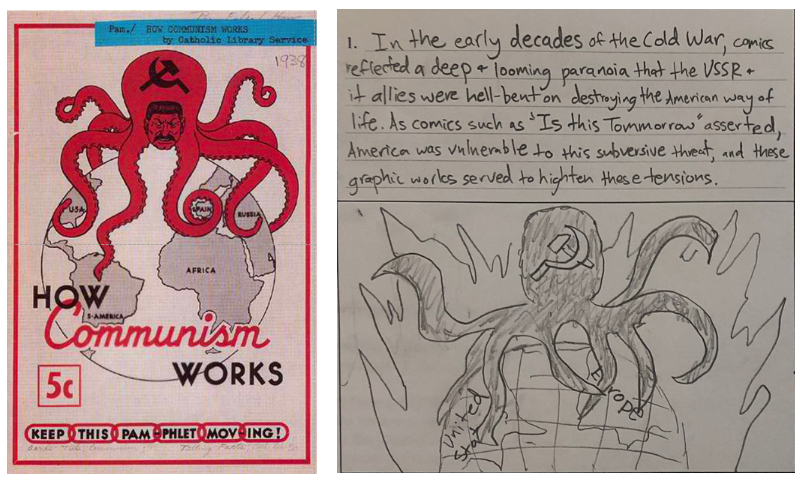

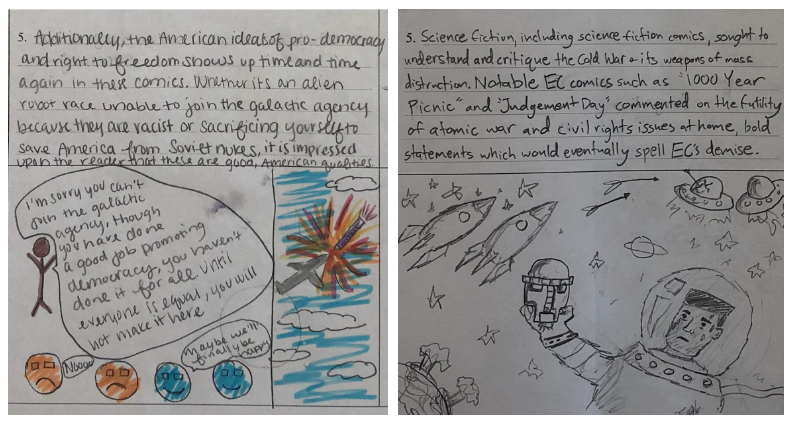

For example, we began the course by analyzing how the “Red Scare” delineated boundaries between acceptable and intolerable social behavior and how, in the process, the anti-communist crusade limited opportunities for those Americans seen as the “other.” We discussed how the Catholic Library Service pamphlet “How Communism Works” from 1938 set conditions for how postwar Americans thought about the threats of communism. Students replicated this “looming paranoia” in their exam answers.

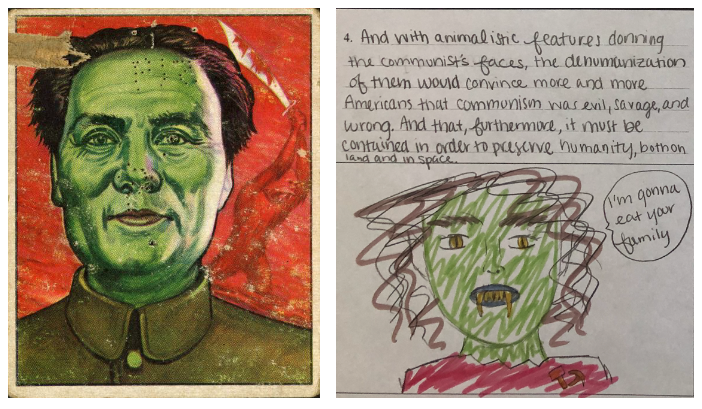

During the semester, we also evaluated how the Bowman Trading Card Company’s card set from 1951, Children’s Crusade against Communism: Fight the Red Menace, informally recruited children into the Cold War contest. These cards—relying on text and imagery, just as the comics did—molded political content for a young audience, helping them understand the ideological terms of the Cold War. Indeed, the card box featured an oath for children to swear: “I believe in God, and the God-given freedom of man…. I am against any system which enslaves man and makes them merely tools of the State.” Students made these connections during the exam. They wrote how the Bowman cards “reinforced conservative views for young audiences,” while replicating imagery that made Fight the Red Menace so appealing to Cold War child consumers.

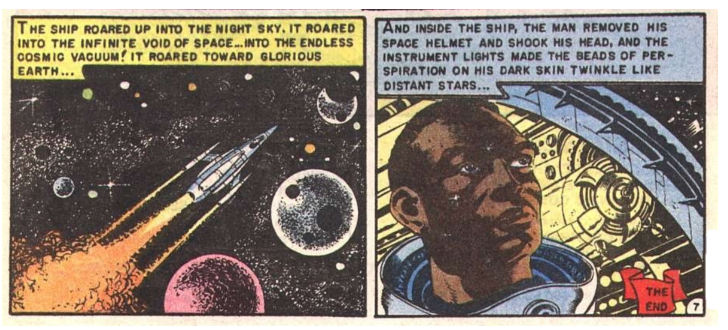

And, thanks to our exploration of EC Comics, we evaluated how at least some pre-code writers and artists used their pages as critiques against a society that was not living up to its potential for achieving social justice and equal rights. We surveyed science fiction comics and the ways in which publishers used them as allegories for the future of race and morality in the United States. We deliberated how EC “dared to get political” and how the company designed racial polemics that could be read not only by children, but by adults as well.

In discussing EC’s “Judgment Day!” from 1953, for instance, we saw future worlds where racial prejudice impeded the progress of democracy, surely an issue when placed into the contemporary context of a global struggle against communism. Once more, students stepped up with engaging answers on their exam that demonstrated a grasp of our course objectives and, just as importantly, a level of creativity that might not have been realized in a written exam alone.

By delving into Cold War comics, my students and I have had the unique opportunity to evaluate how these visual arts depicted race, identity, gender, and social justice during a time when many US citizens believed they were engaged in an existential struggle between good and evil. In every class period, we’ve discussed both the history of the Cold War and how contemporary comics reflected and shaped Americans’ understanding of that time period.

Moreover, early in our course, we read a selection from Harriet E.H. Earle’s Comics: An Introduction, in which see argues, persuasively, that comics “draw on the traditions of visual political commentary.” I think she’s right. The challenge for assessing students’ grasp of this important concept lies in how best to evaluate their progress toward realizing course objectives that speak both to the history of a certain time period and how comics depict that history as it is unfolding.

I might suggest that if we do “frame” our exams in a way that does mirror the medium, we can craft assessment mechanisms like a mid-term exam that evaluate progress and performance while also allowing students to be as creative as they wish to be.

Gregory A. Daddis is a professor of history at San Diego State University and holds the USS Midway Chair in Modern US Military History. Daddis specializes in the history of the Vietnam Wars and the Cold War era and has authored five books, including Pulp Vietnam: War and Gender in Cold War Men’s Adventure Magazines (2020) and Withdrawal: Reassessing America’s Final Years in Vietnam (2017). He has also published numerous journal articles and several op-ed pieces commenting on current military affairs, to include writings in the New York Times, the Washington Post, and National Interest magazine. He is the recipient of the 2022-2023 Fulbright Distinguished Scholar Award, Pembroke College, University of Oxford.

Written by

Dr. Elizabeth Pollard, Professor of History

In my exploration of comics from the last century that deal with ancient Rome, Valor has supplied a fascinating stop along the way. EC Comics’ Valor took its readers to ancient Rome in every issue of its run. The plots are martial, either in the gladiatorial arena or on the battlefield, or both. Men maneuver for power, and women play roles as victim, seductress, political villain, or all three. Surprising, if slightly-off, historical details abound: the range of armor (e.g. lorica segmentata) and fighting styles of different gladiators (e.g. a caestus-wearing fighter), the names of regions (e.g. Calabria, Tuscany, Iberia, and Parthia) and even specific legions (Valeria Victrix), mention of the Lupercal (a Roman holiday), detailed ranks and fighter-types in the military (from primus pilus to hastati, velites, and triarii, as if right from the pages of second-century BCE historian Polybius). Even so, genuine historicity is profoundly lacking. In Valor, ancient Rome became a backdrop, literally and figuratively, for the sumptuous art and complicated storylines with the “snap” endings for which EC was known… and offered an opportunity for EC to go in a “New Direction” for a short time.

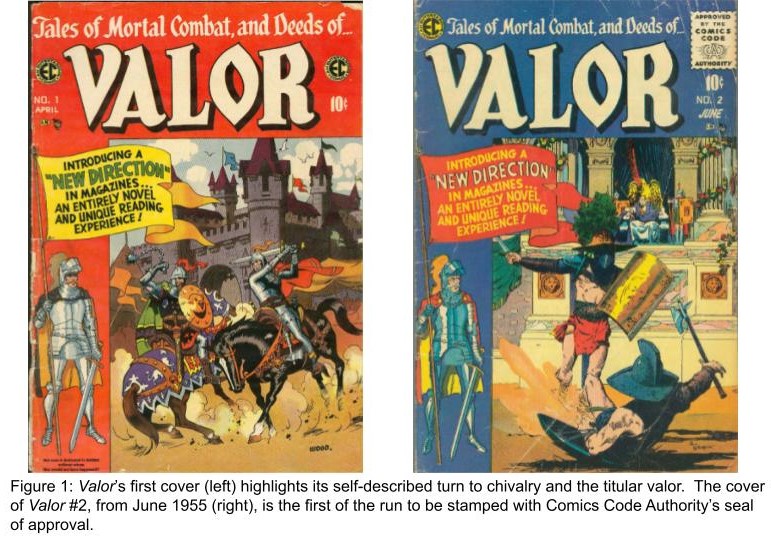

Post-Code Context: Entertaining Comics, aka EC Comics — with its Tales from the Crypt, Vault of Horror, Haunt of Fear, Weird Science, and SuspenStories (of the Crime and Shock variety) — launched Valor in April 1955. Formally-titled Tales of Mortal Combat and Deeds of Valor, the series ran every-other-month for five issues from April through December of that year. Why is the 1955 date significant? Sure, it’s the year that Disneyland opened its gates and Davy Crocket’s coon-skin cap was all the rage. But in terms of comics history, it’s also the year after the Comics Code Authority (CCA) was established, by means of which the comics industry endeavored to oversee its own “decency.” [An earlier attempt in 1948 at self-regulation, by the Association of Comics Magazine Publishers, had not found much traction.] The ideas expressed in Frederic Wertham’s indictment of the comics industry for its purported contribution to juvenile delinquency in Seduction of the Innocent (April 1954) had already found wide circulation in the Ladies Home Journal as “What Parents Don’t Know About Comic Books” (1953) by Wertham himself and earlier, in “Horror in the Nursery” (Judith Crist, in Collier’s Magazine in March 1948). So great was the moral panic over comics, such as those on EC’s publication list, that the U.S. Senate launched an investigation in 1954. [See Amy Kiste Nyberg, Seal of Approval: The History of the Comics Code, 1998.] With vivid examples, Wertham and his supporters had endeavored to convince parents that comics — through their plots, images, advertisements, and more — were teaching, in step-by-step textbook fashion, their children how to be criminals; more specifically, their sons how to be rapists and killers. EC’s response? Six ‘New direction’ titles lauding other, respectable occupations both current and historical: Impact, Psychoanalysis, MD, Extra!, Aces High, and Valor.

The cover of Valor #1 features a knight holding a banner: “Introducing a ‘New Direction’ in magazines… an entirely novel and unique reading experience!” On the first page of the first issue, the editorial Round Table prided itself on having respected the readers’ “taste … judgment… standards, and… intelligence” with its previous, i.e. pre-CCA (although not explicitly named), EC publications. Responding directly to the critiques that had been leveled against the industry, the editors defended EC’s use of “only the best art work available” and “the clearest lettering” in their production of “stories worthy of being read.” And, they proudly heralded their development of the “‘caption-balloon’ method of narration” and the “‘snap’ ending to each story.” While conceding that many of their now-defunct titles had become a “topic of debate, criticism, and censure,” the editors maintained that they had been giving the readership what it wanted. And now, they claimed, they would continue to do so, but instead with “stories of Chivalry, Mortal Combat, Deeds of Daring, Action, and Adventure… against a background of The Past.” Readers’ first glimpse of this new direction? Turning the page… “The Arena.”

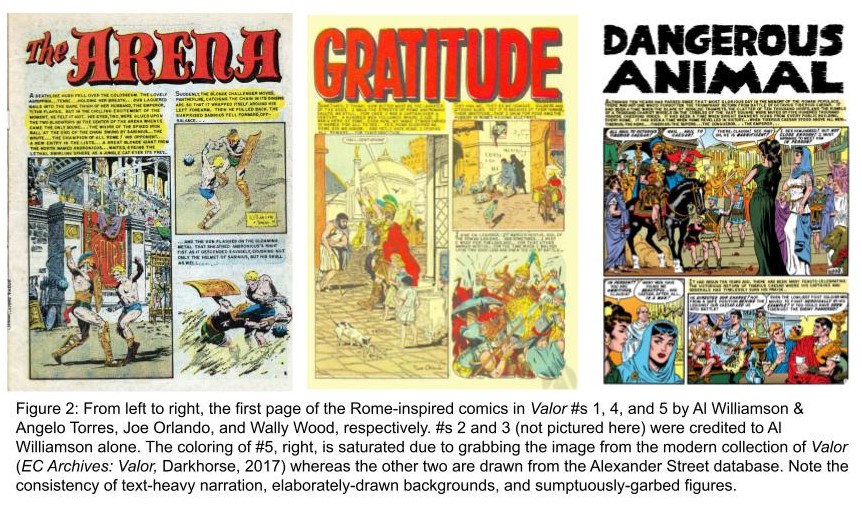

The Creators: The Rome-inspired stories in Valor are the work of the so-called Fleagles, the team of young and collaborative creators making their mark at EC Comics in the 1950s (See Greg Theakston, The Fleagles: The Classic EC Artists, 2011). Three of the five titles — The Arena (#1), The Champion (#2), and Cloak of Command (#3) — credit Al Williamson (with Angelo Torres listed as co-creator of #1). Gratitude (#4) is credited to Joe Orlando, of “Judgment Day” fame (Weird Fantasy #18, March/April 1953). And “Dangerous Animal (#5) is credited to the prolific Wallace “Wally” Wood. Even with the diverse creative team, all five Rome-inspired stories have a similar look and feel: text-heavy plot-description, intricately drawn figures with elaborate clothing (from military armor to matronly robes), historically-evocative (if not completely accurate) backgrounds, to name just a few of the continuities.

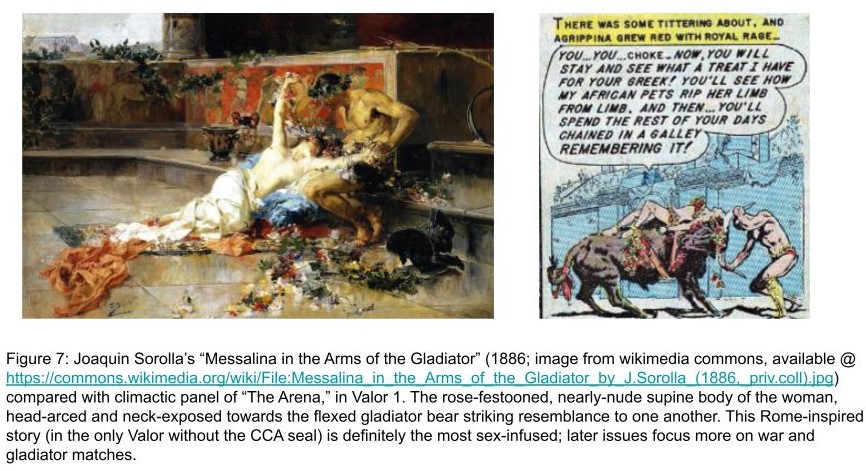

Historicity?: While the intricate art of the comics is a highpoint, the precise historicity is anything but. In the opening editorial “Round Table,” the editors had proclaimed that Valor would take place “against a background of The Past” and that the stories would “relive a thousand… thrilling moments in bygone but memorable historical periods” (Valor #1, p. 1). It’s all too easy for a Roman historian to pick apart the historical flaws in a comic created by non-historians for a non-historical purpose, but one does wonder where the Fleagles were getting the content — names, plotlines, look, etc. — they did include. To explore just the plotline of #1, from the first panel in “The Arena” in which the “lovely Agrippina” breathlessly gazes down at a gladiator match digging her nails into the thigh of her husband… Titus Flavius (not Germanicus, in the case of the “real” Agrippina Maior; nor Domitius Ahenobarbus, Passienus Crispus, or Claudius, in the case of her daughter, the “real” Agrippina Minor), the reader knows the comic is not making an attempt at genuine historicity. And yet the scenario — that of an upper-class woman drawn to a gladiator — is not far-fetched. Graffiti from Pompeii extolled the sexual prowess of gladiators (e.g. Celadus, the “girls’ heartthrob” from the Ancient Graffiti Project @ http://ancientgraffiti.org/Graffiti/themes/Gladiators) and the empress Faustina the Younger, wife of Marcus Aurelius, once fell in love with a gladiator, according to hostile source-material (Historia Augusta, Life of Marcus Aurelius 19). Beyond the first-century CE gladiator love story in “The Arena,” there’s what appears to be a first-century CE story of loss and recognition [in “The Champion,” set in the reign of Caligula (37-41 CE) and flashing back to twenty of so years earlier; a first-century BCE (or CE?) Iberian conflict in “Cloak of Command”; a veteran of Legio Valeria Victrix interacting with General Belisarius and Emperor Justinian (from 6th century CE) in “Gratitude”’s scenario that is suited to a mix of the early first century BCE (slave revolts in the Italic countryside) and later Rome (Gothic invasion); and finally, in “Dangerous Animal,” an entirely ahistorical scenario in which the emperor Tiberius (14-37 CE) dies fighting a gladiator who becomes emperor in Tiberius’s stead. Misguided and mistaken, nonetheless a surprising swath of Roman “history” covered for in such a short-lived comic!

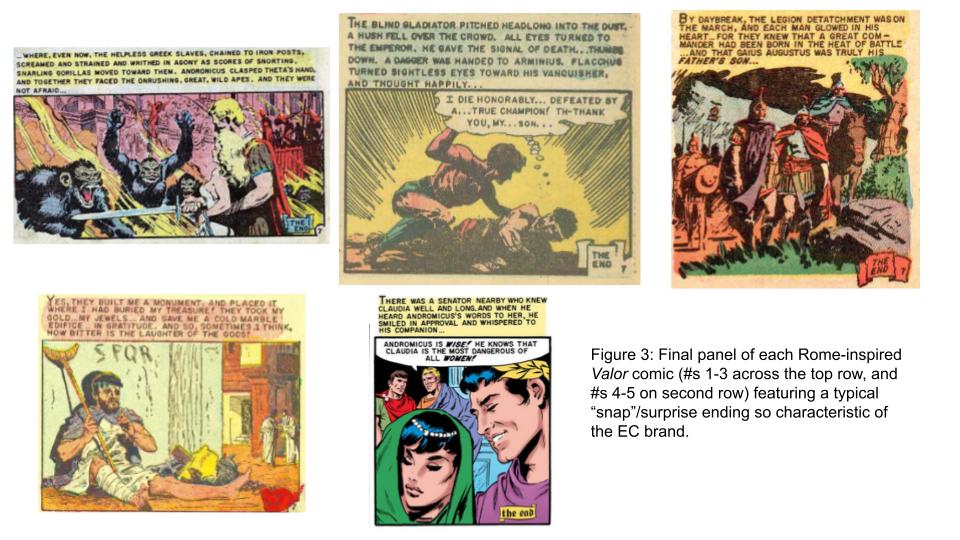

Snap-Endings and Visual Reference: Each of the comics has the “snap” ending for which EC was known: in Williamson and Torres’s “Arena” (#1), the freed-gladiator-turned-captain jumps into the arena to die with the slave-woman whom he had fallen in love with; in Williamson’s “The Champion” (#2), the freed-but-going-blind gladiator chooses to return to the arena and is killed by his long-lost son; in Williamson’s “Cloak of Command” (#3), the young leader recognizes that he must listen to his war-grizzled commanders; in Orlando’s complicated “Gratitude” (#4), a soldier who buries wealth he stole from those he was supposed to protect, refuses wealth from the emperor when he is praised for his valor in battle, and then loses his ill-begotten buried wealth when the emperor puts up a statue in his honor and finds the buried treasure in the process; and in Wood’s “Dangerous Animal” (#5), the final panel makes clear that the gladiator-turned-emperor recognizes that the most dangerous animal of all is not the panthers, tigers, or even elephants against whom he fought, but rather the scheming seductress Claudia.

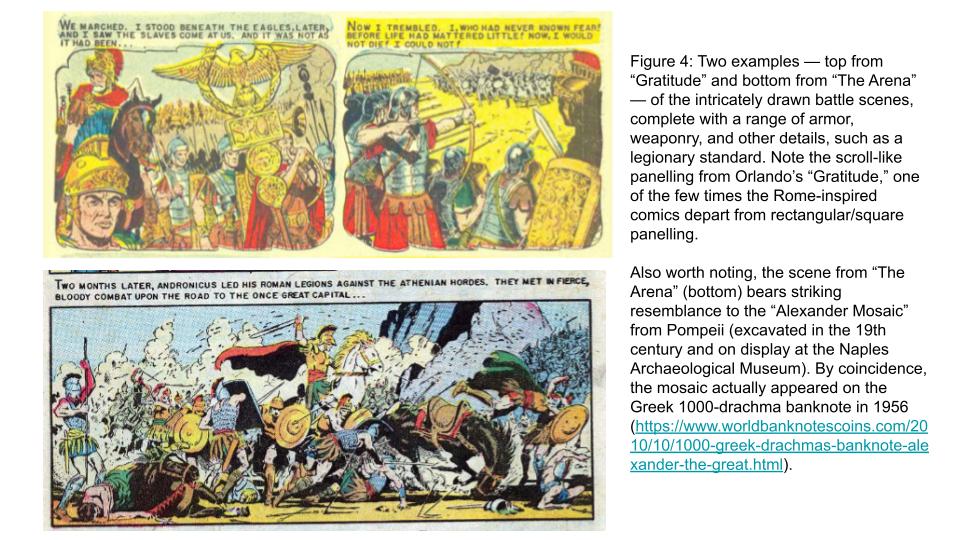

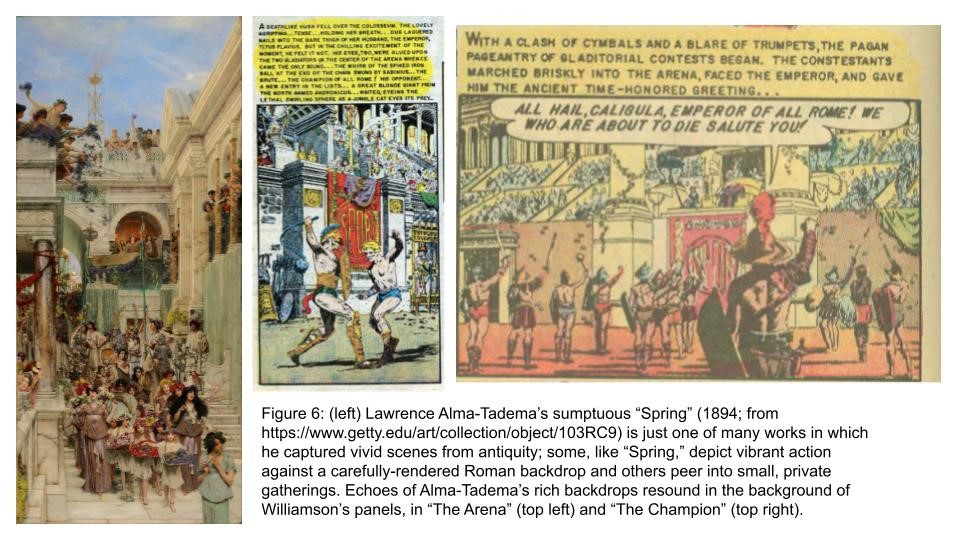

Any study of these comics must examine their artistic style. The backgrounds are truly spectacular, full of carefully drawn Roman temples and intricate crowd scenes. Battle scenes are rendered with a balance of detail and martial fury. Most of the paneling is quite simple, squares and rectangles with prose captions to drive the narrative and plot-rich word balloons. Orlando’s “Gratitude,” however, takes on the usual device of the regular, hard-edged rectangular panels on the first page (when the comic’s story is narrated in the present) and then shifts to irregular, almost scroll-like, panels as the narrator recounts events in the past, with a return to the square paneling at the end when the narrator snaps back to the present. A similar device, shifting from the square panels (for the present time of the comic’s storyline) to borderless panels for flashback and reverie/events-out-of-time had been used to good effect by Williamson in “The Champion.”

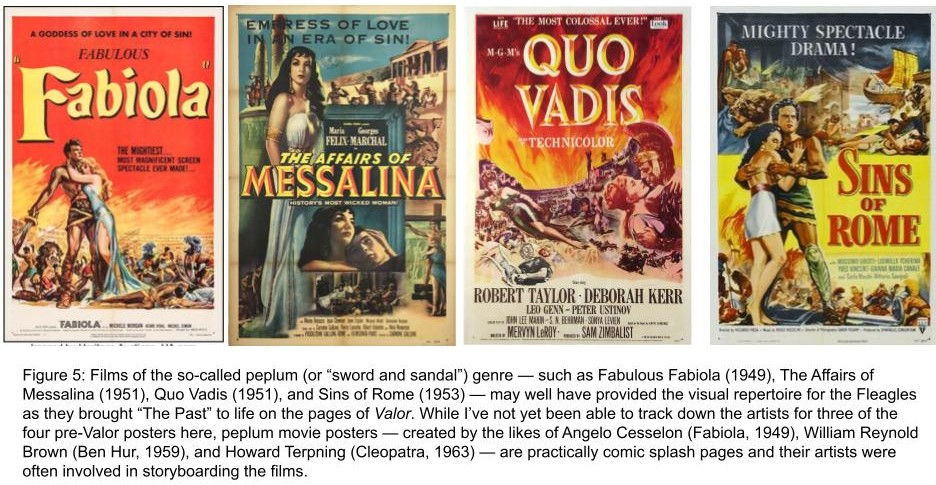

The detail rendered by the Fleagles’ artistry spurs one to wonder what were their reference points: the sword and sandal flicks (or peplum films) already dominating the silver screen or, perhaps art that dealt with similar themes? When Williamson, Torres, Orlando, and Wood were working on these comics, movie-going audiences had recently been captivated by films like Fabiola, Quo Vadis, The Affairs of Messalina, and Sins of Rome. It’s not hard to see the visual continuity between the lavish silver-screen productions and the panels of Valor. If not this eye-candy, relatively recent artwork (from Alma Tadema to Joaquin Sorolla) and even ancient mosaics, whose excavations often made headlines (for instance the excavation of the Romerhalle in Bad Kreuznach in the late 19th century, with its detailed gladiator mosaic), may well have fueled the imagination of the Fleagles in their own drawing of ancient Rome.

New Direction, New Influence?: Whatever the reference point, whatever the historical (or not) source material, in EC Comics’ Valor, young readers were treated to a pseudo-historical feast fit for an emperor! EC found a way to preserve its blend of violence and sexuality, mystery and morality, in a way that flew under the radar of the Comics Code Authority and titillated readers in 1955. In the third issue of Valor, readers’ letters to the editorial “Round Table’’ teemed with enthusiasm for EC’s “new direction.” One Ronald Ecker wrote: “After reading the first issue of Valor, it was inevitable that I send in my sheet of papyrus and compliment you on your great achievement. It is astounding what you guys can do with colored panels and captions. You have brought the reader the chivalrous days of past eras never to be forgotten; not in the simple way of your competitors, but with superb art work, elaborate drawn by the best comic artists in the business.” Lest one think that Ecker was a fictitious letter-writer, it appears that young comic-reading Ron of Palatka, Florida grew up to be retired-librarian Ron of Palatka Florida, who himself went on to write screenplays with a flare for historical drama (https://writers.coverfly.com/profile/writer-ae787f48b-151). EC’s Valor comics no longer could be accused of teaching young people how to commit violent crime; but (young Ron, perhaps, excepted), the comics could not exactly be accused of teaching young readers their Roman history, either. Nonetheless, the Fleagles’ work on Valor — with its truly remarkable scenes that envisioned the glory of ancient Rome and its historically evocative, if not accurate, stories — is nothing short of Herculean.

Elizabeth Pollard is Distinguished Professor for Teaching Excellence at San Diego State University, where she has taught Roman History, World History, and witchcraft studies since 2002. She co-directs SDSU’s Center for Comics Studies and recently debuted a Comics and History course exploring sequential art from the paleolithic to today. Pollard is currently working on two comics-related projects: an analysis of comics about ancient Rome over the last century and a graphic history exploring the influence of classical understandings of witchcraft on their representations in modern comics. Pollard has co-authored a world history survey (Worlds Together, Worlds Apart) and has published on various pedagogical and digital history topics, including DH approaches to visualizing Roman History.