Written by

Dr. Elizabeth Pollard, Professor of History

For one of my current research projects, I’ve been accumulating comics from the last century that engage in some way with ancient Rome. Among the odder comics I have stumbled across in that enterprise has been “The Dart.” The Dart and his boy side-kick Ace appear in all but four of the twenty issues of Weird Comics, a Fox Feature Syndicate publication. From their inception, Dart and Ace enjoyed a long run on the cover of every Weird Comics and as the first title in each issue, until May 1941 (Weird Comics 14) when the patriotic “Eagle” took the cover for the first time since Dart and Ace premiered. The rising tide of World War II in Europe and North Africa offers the obvious explanation for the ultra-American, flag-draped Eagle’s eclipsing of a reincarnated Roman superhero, especially given Italy’s increasing role in the war. Germany, Italy, and Japan had officially become the Axis powers via the Tripartite Pact on September 27, 1940. What’s really surprising, in that 1940/41 context, is that Dart stayed on the cover of Weird Comics for as long as he did!

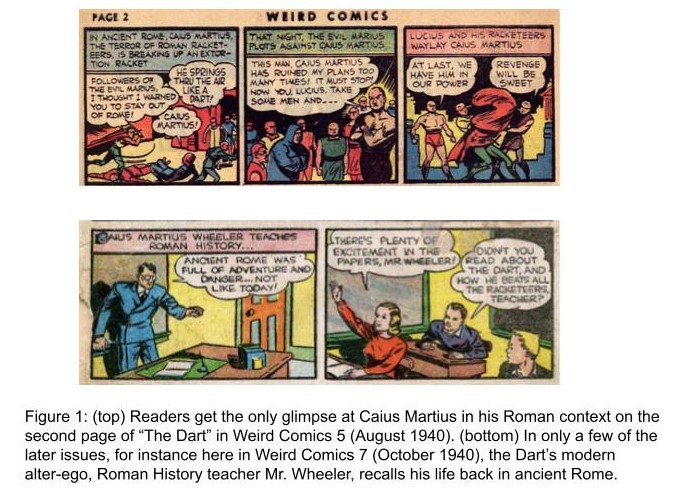

So, just who is this Dart? The full-page splash on the Dart’s first issue includes a text box that first introduces us to this “new” hero: “Out of the hidden shrouds of history comes a legendary man who dedicates his life to fight crime and racketeers — the invincible Roman, Caius Martius, who takes the name: The Dart” (Weird Comics 5, August 1940). Turning the page, readers were immersed for one page — in fact, the only page of the entire sixteen-issue series — that takes them back to Caius Martius’ origins as “the terror of Roman racketeers” in the early first century BCE. Readers learn that Caius was a supporter of Sulla, who is presented here as the good guy, not the death-warrant-issuing dictator whose bloody reign resulted in the murder of thousands of Romans in the 80s BCE. Sulla’s rival Marius (here the “evil” guy) orders his henchman Lucius to do away with Caius Martius. Sulla’s troops are too late to save Caius before he is dissolved into a stone table by a hooded ritual expert. The magical spell is supposed to last 2200 years; and at the bottom of the page the reader’s eye moves from a panel in which his would-be rescuers mourn “Rome’s saddest loss” to a panel in which 20th-century museum-goers scatter in fear as the body of Caius Martius rematerializes on the same stone table. Nevermind that the math is incorrect (an early 80s BCE spell that lasted 2200 years would expire ca. 2110, not 1940); Caius leaps right into action against tommy-gun wielding gangsters who have orphaned a boy named Ace Barlow, whom we see mourning his parents shot dead in the street (shades of Bat-Man’s origin in DC 33 from late September/November 1939). Ace becomes Dart’s wooden bat-wielding side-kick. When he’s not hurling his Roman gladius like a projectile, the Dart wields his signature weapon in his right hand, stabbing cars, punching through walls, skewering the skulls of criminals (quite vividly), and even collapsing a bridge.

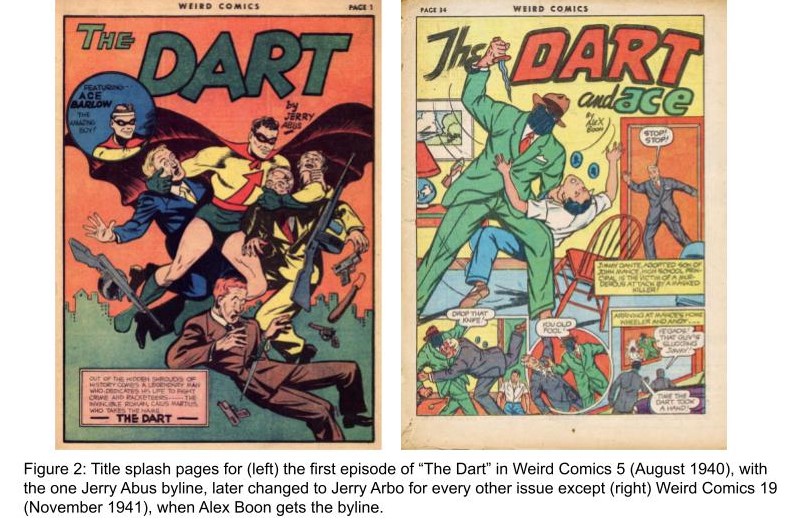

To whom should we offer our thanks for this gladius-brandishing Roman “racket buster”? The signatory author of “The Dart” ranges from Jerry Abus (Weird Comics 5) on the splash page of the first Dart comic; to Jerry Arbo (Weird Comics 6-18 and 20), with one attributed to Alex Boon (Weird Comics 19, November 1941). The consensus across various comics databases is that Jerry Abus/Arbo is a house name or pseudonym used by Luis Cazeneuve (1908-1977), an Argentinian comic artist known for his work on “Quique, el Niño Pirata” in Argentina and then later in the U.S., creating work for National/DC (e.g. Aquaman), Harvey Comics (e.g. Phantom Sphinx), and other Fox Feature Syndicates (e.g. Blue Beetle). [see Luis Cazeneuve” in Lambiek Comiclopedia (updated 1-18-2018); https://www.lambiek.net/artists/c/cazeneuve_l.htm]. Alex Boon, the byline for Dart in Weird Comics 19, is likely Alex Blum, a Hungarian-American who worked for Eisner & Iger at the same time as Cazaneuve (late 1930s and early 1940s) — notably drawing “Samson” and “Eagle” and going on to work on Classics Illustrated, including Homer’s Iliad (#77) and Midsummer Night’s Dream (#49). [see Alex Blum,” in Lambiek Comiclopedia (updated 7-15-2021) and CCS Books, https://ccsbooks.co.uk/]

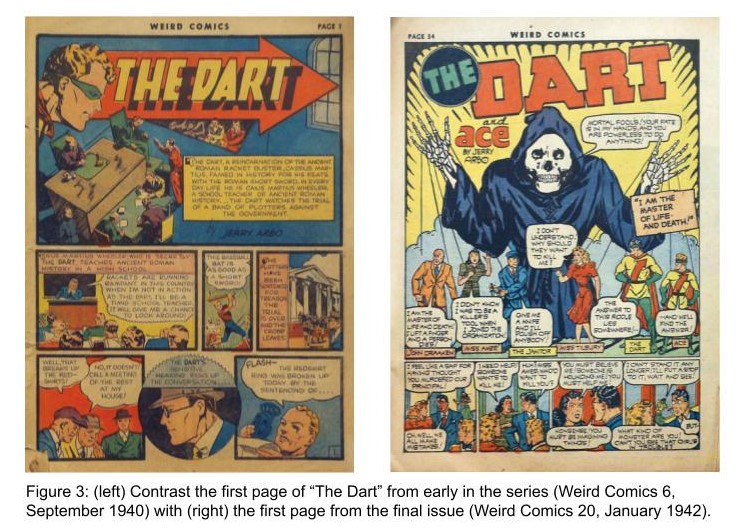

Although attributed to the same name for nearly every issue, the style changes dramatically across the sixteen appearances of “The Dart,” from his debut in August 1940 to his last adventure in January 1942. This stylistic change is easily glimpsed with the juxtaposition of a first page from early in the run with one from ten months later (Figure 3). From Dart’s second appearance in Weird Comics 6 (September 1940) through through Weird Comics 16 (July 1941), the first page of each Dart comic includes a half-page scene-setter, with an introductory text box reminding readers of the Dart’s past as “ancient Roman racket buster Caius Martius” (although in Weird Comics 16, he’s mis-named as Cassius Martius!). Beginning with Weird Comics 17, in August 1941, and through the end of the run in January 1942, the text box reminding the reader of Mr. Wheeler’s ancient Roman past life disappears and the first page becomes far splashier.

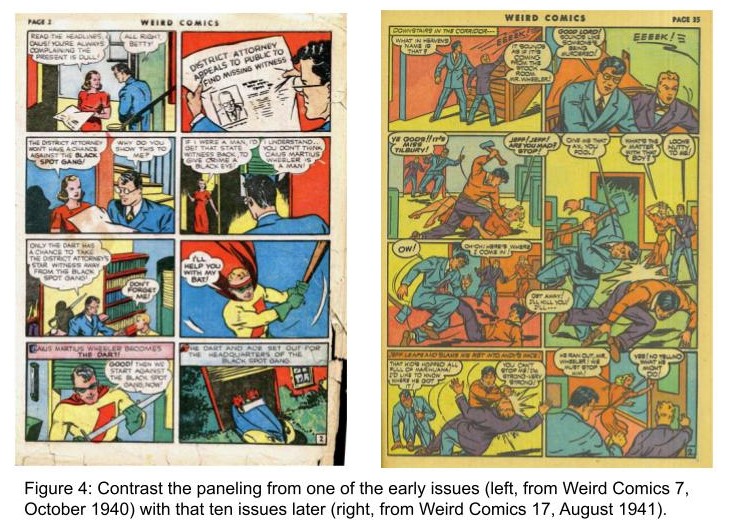

The change in “The Dart”’s style across its run is also manifest in its panel scheme (Figure 4). A simplistic two by four framing pattern characterizes the majority of pages throughout the sixteen issues of “The Dart.” Each panel neatly contains the figures and word balloons, as the action plods forward from scene to scene. Towards the end of the run (mid 1941), however, the paneling becomes more complex. Word balloons and body parts extend beyond the panel, drawing the reader’s eye to the next stage of the action and even pointing the way, when the paneling becomes more complex. For instance, on one page from “The Pushcart Drug Pusher” (August 1941) an ax provides the continuity from panels 3 to 4. Then Mr. Wheeler’s knee points the reader to the fifth panel. The hand of Mr. Wheeler’s punched fellow teacher then points the way from panels 5 to 6. Jeff Dean’s foot bleeds from panel 4 to 7, essentially escaping that panel into the last panel on the page, where he has evaded capture by the Dart. What might have precipitated this change? No doubt, the dynamic and imaginative framing, energy, and action that leaped off the pages of Jack Kirby’s revolutionary Captain America #1 in March 1941 had an immediate influence on Luis Cazeneuve, the artist behind the Jerry Arbo house-name ascribed to all but a few of the issues of “The Dart.”

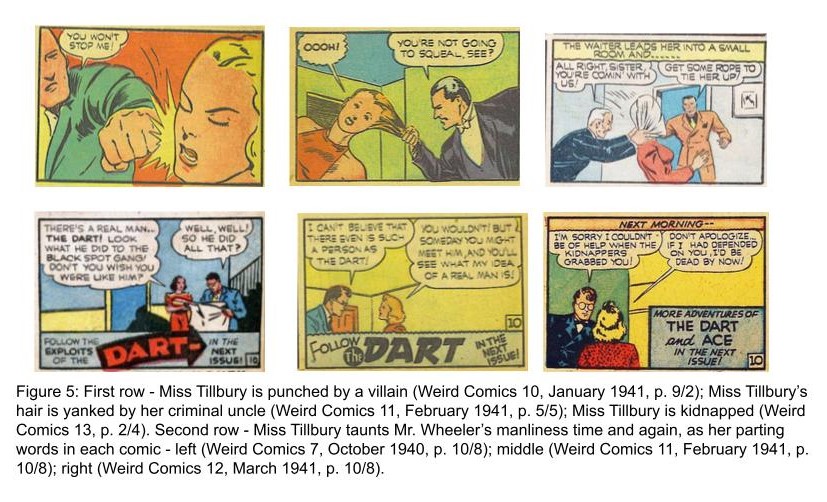

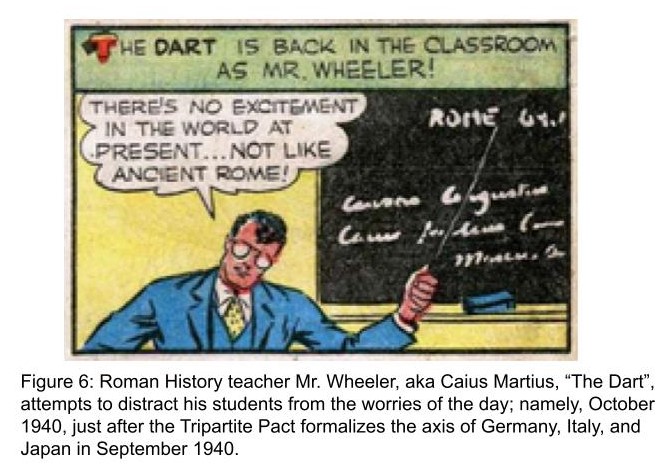

There is much more that I’ll say when I incorporate “The Dart” into my larger project of ancient Rome in comics, but a few final issues to note. Particularly shocking to a modern reader is the casual, repeated, and explicit violence to Miss Tillbury (Figure 5). Her life is threatened many times; she is punched; she is yanked around by her arm and hair; and she is abducted. This level of disturbing violence in comics is one of many issues the Comics Code Authority of 1954 sought to minimize. Paired with this violence against women is an ongoing discourse on masculinity… in particular, the much-abused “love interest” and fellow teacher Miss Tillbury’s frequent impugning of alter-ego Mr. Wheeler’s manliness, in favor of the Dart’s. Miss Tillbury needles Mr. Wheeler: “If I were a man, I’d get that state witness back” and at the end of the same issue, “There’s a real man… The Dart! Look what he did to the Black Spot Gang! Don’t you wish you were like him?” (Weird Comics 7, October 1940, p. 2/4 and p. 10/8). And as if that weren’t enough, in the next issue Mrs. Tillbury responds to Mr. Wheeler’s request to take her to dinner with “Thank you… But I prefer to go out with men… Good morning!” (Weird Comics 9, December 1940, p. 1/3). In that same issue, Tillbury tells Dart: “I wish Gaius Martius Wheeler were a man… like you!” (Weird Comics 9, p. 6/8). After Mr. Wheeler expresses his incredulity that someone so brave as the Dart exists, Miss Tillbury exclaims: “[S]omeday you might meet him and you’ll see what my idea of a real man is!” (Weird Comics 11, February 1941, p. 10/10). Miss Tillbury’s repeated maligning of Mr. Wheeler’s masculinity continues through to the end of the run, with parting shots like “… if I had depended on you, I’d be dead by now” (Weird Comics 12, March 1941, p. 10/8) and “Whenever a man’s help is needed, you’re not around! I’m getting tired of this!” (Weird Comics 18, September 1941, p. 10/9) and even her last words in the last issue “I’ve seen jelly fish [sic] display more courage than you!” (Weird Comics 20, January 1942, 10/8). This discourse on manliness and even absent masculinity is particularly striking as the United States was considering full-on engagement in World War II. Perhaps readers lost their interest in such taunting after Japan’s attack on the U.S. at Pearl Harbor. “The Dart,” and the long-emasculated Mr. Wheeler, sees only one more issue after that infamous day. Mr. Wheeler’s claim to his students, “There’s no excitement in the world at present… not like ancient Rome” in October 1940 — just after the Tripartite Pact formalized the Axis powers — likely rang too false once thousands of American soldiers were killed and wounded on December 7, 1941.

Elizabeth Pollard is Distinguished Professor for Teaching Excellence at San Diego State University, where she has taught Roman History, World History, and witchcraft studies since 2002. She co-directs SDSU’s Center for Comics Studies and recently debuted a Comics and History course exploring sequential art from the paleolithic to today. Pollard is currently working on two comics-related projects: an analysis of comics about ancient Rome over the last century and a graphic history exploring the influence of classical understandings of witchcraft on their representations in modern comics. Pollard has co-authored a world history survey (Worlds Together, Worlds Apart) and has published on various pedagogical and digital history topics, including DH approaches to visualizing Roman History.