Written by Gregory A. Daddis, USS Midway Chair in Modern U.S. Military History, San Diego State University

Teaching a Cold War comics course for the first time has reinforced what I have suspected for a long time—comics are some of the most insightful cultural products of post-World War II era.

Cold War era comics spoke to fundamental issues of American identity in a rapidly changing postwar society. They illustrated the fears that drove domestic and foreign policies at a time when evil, godless communists seemed lurking behind every dark corner. They expressed anxieties over living in the atomic era, when the possibility of nuclear Armageddon appeared ever more likely each time children ducked and covered under their school desks. And they reflected the possibilities and limits of achieving true social justice when many Americans’ civil rights were being contested by defenders of a stratified prewar status quo.

These representations of Cold War American society informed my course design for HIST 580, “Comics and Cold War America,” taught in the 2022 fall semester at San Diego State University. The course supported a National Endowment for the Humanities grant, “Building a Comics and Social Justice Curriculum,” co-directed by Elizabeth Pollard and Pamela Jackson, both of whom also lead our university’s Center for Comics Studies.

How comics, as cultural products, influenced Americans’ understanding of social justice issues helped shape the fundamental objectives that I hoped my students and I would achieve by course end. Though our study of comics, I sought ways in which we might be better equipped to articulate the domestic impact of the Cold War in the United States and the ways in which this global contest affected American citizens’ conceptions of culture, society, and social justice. And I hoped that our critical engagement with comics as Cold War cultural products would help us evaluate how they communicated the relationship between word and image.

But how to assess student performance and progress while trying to achieve two course objectives simultaneously—evaluating Cold War American society and culture while also engaging with comics as visual cultural products?

The answer, for me at least, was to mirror the medium.

For my mid-term exam, I provided my students with what I thought was an innovative prompt that would allow them to be more creative than simply writing a traditional essay:

“You have been asked by the editor of the Journal of Comics and Culture to develop a pictorial storyboard for a new feature titled “The Cold War at Home and Abroad.” The editor would like you to explain to the journal’s readership how Cold War comics demonstrated a close relationship between US foreign and domestic policies from 1945 to 1965. To do so, develop your story based on the readings from the first half of our course.”

I then offered them instructions for how to complete the exam:

“You must create your storyboard in six successive panels, an example of which is seen below. The top half of the panel should be used for a written narrative while the bottom half should be used for graphic illustrations. Be creative but remember to focus on making an argument and supporting that argument with historical content and analysis. As each panel’s written portion should comprise a full paragraph, ensure you write using complete sentences. Your drawings should support or enhance your written narrative. Manage your time wisely. Have fun.”

Along with the prompt and exam instructions, I attached an 11×17 paper that had six panels—two rows of three columns—laid out consecutively as a reader might see in a comic.

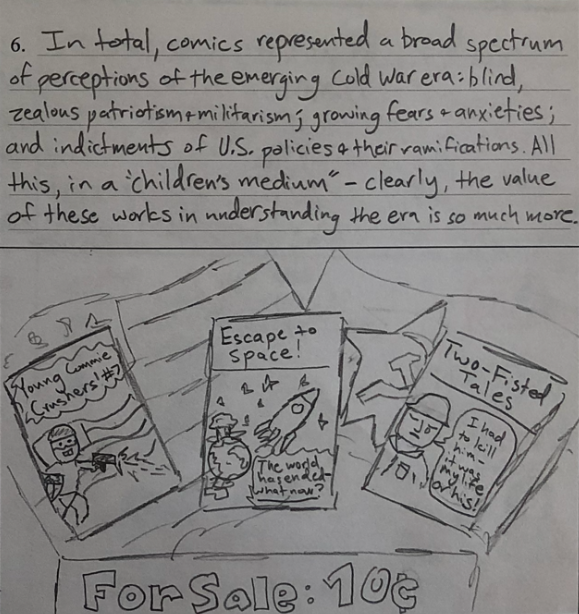

The results showcased how students not only were capable of evaluating Cold War comics on their own merits, but also of expressing their ideas in both written and visual form.

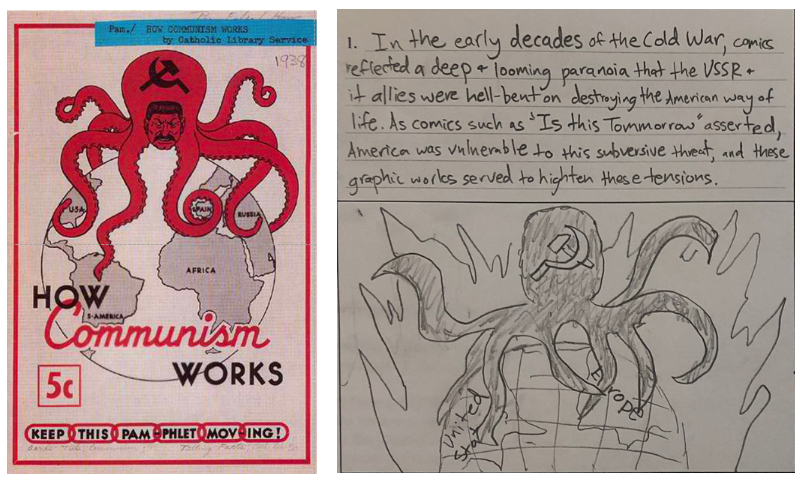

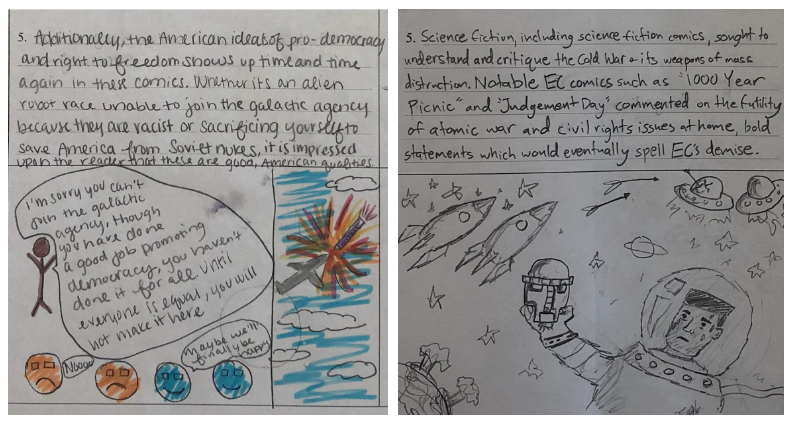

For example, we began the course by analyzing how the “Red Scare” delineated boundaries between acceptable and intolerable social behavior and how, in the process, the anti-communist crusade limited opportunities for those Americans seen as the “other.” We discussed how the Catholic Library Service pamphlet “How Communism Works” from 1938 set conditions for how postwar Americans thought about the threats of communism. Students replicated this “looming paranoia” in their exam answers.

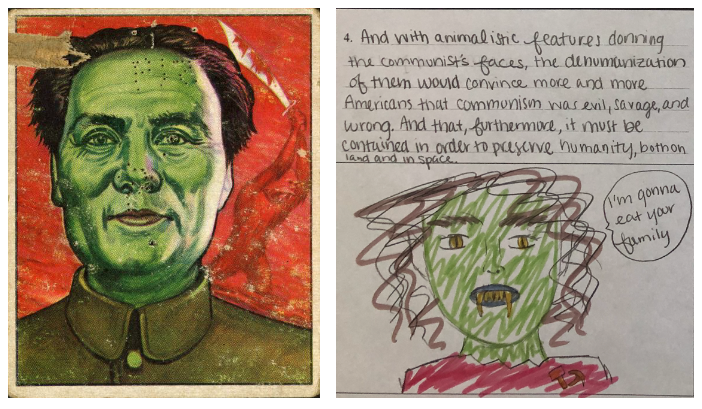

During the semester, we also evaluated how the Bowman Trading Card Company’s card set from 1951, Children’s Crusade against Communism: Fight the Red Menace, informally recruited children into the Cold War contest. These cards—relying on text and imagery, just as the comics did—molded political content for a young audience, helping them understand the ideological terms of the Cold War. Indeed, the card box featured an oath for children to swear: “I believe in God, and the God-given freedom of man…. I am against any system which enslaves man and makes them merely tools of the State.” Students made these connections during the exam. They wrote how the Bowman cards “reinforced conservative views for young audiences,” while replicating imagery that made Fight the Red Menace so appealing to Cold War child consumers.

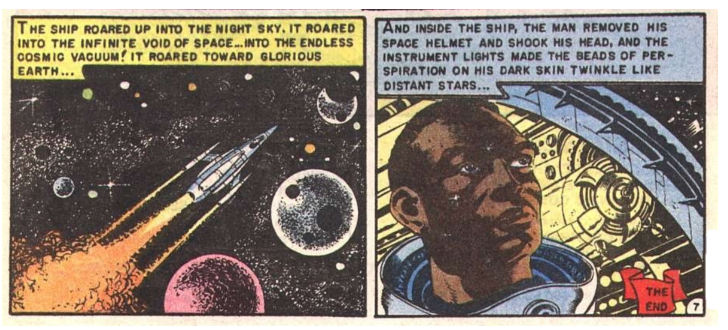

And, thanks to our exploration of EC Comics, we evaluated how at least some pre-code writers and artists used their pages as critiques against a society that was not living up to its potential for achieving social justice and equal rights. We surveyed science fiction comics and the ways in which publishers used them as allegories for the future of race and morality in the United States. We deliberated how EC “dared to get political” and how the company designed racial polemics that could be read not only by children, but by adults as well.

In discussing EC’s “Judgment Day!” from 1953, for instance, we saw future worlds where racial prejudice impeded the progress of democracy, surely an issue when placed into the contemporary context of a global struggle against communism. Once more, students stepped up with engaging answers on their exam that demonstrated a grasp of our course objectives and, just as importantly, a level of creativity that might not have been realized in a written exam alone.

By delving into Cold War comics, my students and I have had the unique opportunity to evaluate how these visual arts depicted race, identity, gender, and social justice during a time when many US citizens believed they were engaged in an existential struggle between good and evil. In every class period, we’ve discussed both the history of the Cold War and how contemporary comics reflected and shaped Americans’ understanding of that time period.

Moreover, early in our course, we read a selection from Harriet E.H. Earle’s Comics: An Introduction, in which see argues, persuasively, that comics “draw on the traditions of visual political commentary.” I think she’s right. The challenge for assessing students’ grasp of this important concept lies in how best to evaluate their progress toward realizing course objectives that speak both to the history of a certain time period and how comics depict that history as it is unfolding.

I might suggest that if we do “frame” our exams in a way that does mirror the medium, we can craft assessment mechanisms like a mid-term exam that evaluate progress and performance while also allowing students to be as creative as they wish to be.

Gregory A. Daddis is a professor of history at San Diego State University and holds the USS Midway Chair in Modern US Military History. Daddis specializes in the history of the Vietnam Wars and the Cold War era and has authored five books, including Pulp Vietnam: War and Gender in Cold War Men’s Adventure Magazines (2020) and Withdrawal: Reassessing America’s Final Years in Vietnam (2017). He has also published numerous journal articles and several op-ed pieces commenting on current military affairs, to include writings in the New York Times, the Washington Post, and National Interest magazine. He is the recipient of the 2022-2023 Fulbright Distinguished Scholar Award, Pembroke College, University of Oxford.